Looking Back on Ten Years of Mountain Bike Innovation

My career has spanned the history of the mountain bike and I can say without hesitation that this past decade has been one of the sport's most dynamic periods of change. Innovations and new standards seemed to pop up monthly, and the controversies they spawned were legion at times. Let's revisit some of them.

Strava

Founded October, 2009, by Mark Gainey and Michael Horvath, the Strava smart phone app was predestined to revolutionize cycling. Think about it; cyclists are predominantly nerdy loners, preoccupied by our levels of fitness and skills, who often train in isolation and are competitive to the point of diagnosable neurosis. Furthermore, we are habitual liars anytime we discuss our performance and mileage with other cyclists.

Strava turned every trail into a World Cup race course. Our smart phones became a coach, a court of law, a confessional, a hall of fame, and a one-swipe source of self gratification. "If you didn't record it on Strava, it didn't happen," is her mantra. She is cycling's deity of truth, cold, but not cruel. She alone determines our rightful place. She justifies our desire to crush the unworthy, and we bow to her in silence before and after every ride, hoping she will reward us with a cup or a personal best. Strava's unintentional consequences have had both positive and negative effects. On the negative side, riders have become much less willing to slow or move off the trail in consideration for others, and many who would never have lifted a finger to volunteer for trail work are busy grooming technical sections and straightening corners to claw time from their virtual competitors.

On the plus side, Strava has helped move technology forward. The wholesale shift by once-reluctant riders to larger wheels and dual suspension - especially dual-suspension in the cross-country ranks - can be attributed in part to irrefutable data from their own Strava results.

Death of 26-inch Wheels

"Twenty six ain't dead!" There was no reason to utter that phrase back in 2010. The 29er was marginalized as a means for cross-country riders to avoid switching over to dual suspension. The mountain bike's seminal wheel diameter could not be challenged as long as downhill racers and freeriders ruled the roost. Trouble was on the horizon, however, and the throne of the full face helmet would soon fall to the half-shell-and-trail-bike coat of arms. In less than ten years, the 26-inch wheel would be dead to the mountain bike community - survived only by a vestigial population, kept alive by circus performers at pump track and slopestyle venues.

Big wheels, it turns out, actually did roll faster, just like Wes Williams, Gary Fisher, and Chris Sugai said they did. Strava verified that truth, but in spite of the fact that avid trail riders were shouting about their advantages, the world was not quite ready for 29ers - especially in Europe, where many believed that North American brands like Trek and Specialized were shoving 29ers down their throats.

The ensuing battle between 26-inch traditionalists and 29-inch evangelists would soon escalate into an all-out war after bike designers ran into a wall attempting to squeeze more than 120-millimeters of rear-wheel travel from their 29er frames.

The answer was a mid-sized wheel - large enough to gain a more advantageous roll-over than puny 26-inch wheels, but just small enough to gain tire clearance for DH-width rubber and for wheel travel in the neighborhood of 150 millimeters. North American brands called the mid-sized wheel 27.5 inch. European bike makers insisted upon 650b and they ran with it. Three camps were now banging out insults on their keyboards, but 27.5 was the last nail in the coffin for 26-inch wheels.

Enduro is almost all 29er. Here, Shawn Neer helps Team USA earn the gold medal at the EWS Trophy of Nations...

...Downhill racers are still divided. Loic Bruni earned his third World Championship gold on a bike with a 29" front wheel and a 27.5" rear wheel.

One can argue that it was a compromise, but the wholesale adoption of the 27.5-inch standard also was an industrywide confession that larger wheels were better. Once the bitterness of that pill faded and designers optimized kinematics, geometry and fork offsets for larger wheels, 27.5 became the new 26 - and by the end of the decade, the 29er would be anointed as the next to wear the crown. Pinion P1.18 Gearbox

It's hard to believe that ten years ago, most mountain bikes had three chainrings, ten cogs, a front derailleur, and shift levers on both sides of the handlebar. It's even harder to conceive that almost nobody was complaining about that. There was (and still is), however, a vocal band of anti-derailleur activists among us who prayed every day for a sealed gearbox transmission that could forever eliminate the mess and complication we call a derailleur drivetrain.

Salvation came in the form of two German automotive engineers who originally worked for Porsche. Michael Schmitz and Christoph Lermen

created a compact sequential-shift transmission. It required three years to bring it to market, but for many, their Pinion P1.18 gearbox was the breakthrough they had been long awaiting. Launched in 2010, the compact 18-speed transmission offered a whopping 636% range with even, 11.5% steps between shifts - gear spacing that could not be matched by any chain transmission.

Pinion's P1.18 gearbox set a high bar for anyone who dared challenge the derailleur, and it still stands as the best gearbox made today. Pinion followed their 18-speed masterpiece with lighter and even more compact 12- and 9-speed versions, all of which have enjoyed some success in the high-end market place. Most truly innovative products come with a learning curve. Pinion's was its rotary shifting. Ultimately, its weight (2700g to 2200g), moderate drag penalty, and its justifiably high MSRP prevented the Pinion gearbox from displacing the longstanding alternative, so it exits this decade as a reminder that the best way to thin a crowd of enthusiastic fans is to ask them to pull out their wallets and make a substantial purchase.

Chain drives are hobbled by evenly spaced teeth. Pinion attains perfectly spaced gear steps by altering the tooth profiles of the gears. Pinon image

That said, Michael Schmitz and Christoph Lermen's transmission set the bar so high that anyone who does find the materials, financing and technology to best them will most certainly match the performance of the humble derailleur transmission. I hope it will be Pinion who accomplishes this miracle.

The Decade of Dave

Dave Weagle didn't invent anti-squat - race car and motorcycle designers already abided by those rules. Weagle was the Prometheus who brought this fire to the mountain bike. Weagle's successful string of design collaborations with the likes of Turner, Ibis, Pivot and Evil became a wake-up call for bike designers large and small to calculate anti-squat values into his or her suspension kinematics.

Roll back the clock ten years and the you'll discover that the most successful solutions to make a suspension bike pedal well were some sort of lever to lock it out. The modern trail bike was just gaining traction, but bike makers largely relied upon shock and fork suppliers to make them pedal well. Weagle taught us that the frame could do a better job.

Weagle's successful demonstrations of how to trick the bike's rear suspension to counter the lagging mass of the rider became the key that unlocked the long-travel trail bike, which in turn, spurred the most rapid period of successful improvement in the history of the genre. If someone told me back then that I would be able to hop onto a 160-millimeter-travel bike with its rear suspension set soft enough to descend steep, techy trails - and still climb efficiently - I would have laughed. Today, when I roll out for my first ride on any test bike, I expect that level of performance and versatility. It is doubtful that the industry would have achieved this without Weagle's influence.

The Duke of rear suspension, Weagle closed out the decade with his Trust linkage fork. Trust image

Clutch-Type Rear Derailleurs

Shimano surprised the world by adding a one-way friction clutch to the chain-take-up cage pivot of its 2012 XTR Shadow Plus rear derailleur. The innovation - a tiny adjustable band brake, encircling a needle bearing clutch - came out of nowhere, but one ride was all it took to realize its potential to calm the slack side of the chain, which in turn, stabilized shifting performance. Shmano's invention was sorely needed.

One-by drivetrains were just beginning to blow up and with no front derailleur to guide the chain, designers were wrestling to lock down lightweight solutions to keep it in place over technical terrain. The bandage was a smaller, lighter version of the chainguides that downhillers used. The roller clutch, however, meted out just enough chain on the slack side to facilitate shifts, but not enough to allow the chain to escape from the bottom half of the chainring. After the clutch (and the next invention on this list), chain guides became optional equipment.

Unlike Shimano, SRAM was completely invested in the one-by concept, so it came as no surprise that the Chicago brain trust fired back with its own clutch design shortly thereafter. Before and after photographs of riders at speed bear witness to the dramatic improvement the addition of cage-pivot clutches made to chain control. Perhaps more welcome, however, is that bikes run much more quietly now.

The gold anodized clutch lever above the XTR Shadow Plus cage pivot forever changed the rear derailleur. Shimano image

Shimano's first Shadow Plus clutch included a tiny wrench used to adjust the friction band.

Narrow-Wide Chainrings

Launched by SRAM 2012 the narrow-wide concept was originally patented in 1978 by Gehl, an industrial equipment manufacturer. It was SRAM's designers, however, who realized that a combination of the narrow-wide tooth profile and specially shaped tips on the sprocket teeth could be used to feed a writhing bicycle chain smoothly onto a chainring from a variety of angles – a technical coup that virtually eliminated the derailing issues which plagued mountain bike riders for over 30 years.

SRAM will be cited most often for its decision to drop the front derailleur in favor of a wide-range one-by drivetrain - a bold move that was rewarded by their near dominance of the elite and enthusiast level trail bike marketplace. Arguably, the narrow-wide chainring, was SRAM's most important (and most duplicated) innovation. Before narrow-wide, tossed chains were considered to be part of the mountain bike experience. After its debut, the thought rarely, if ever, comes to mind. Remove narrow-wide from the wide-range one-by equation and you throw the drivetrain back to the chain-gadget stone age. Death of the Front Derailleur

SRAM's debut of the eleven speed XX1 one-by drivetrain should have been a guaranteed success. For years, conspicuous numbers of the sport's top athletes had been riding and espousing customized one-by drivetrains. Beyond weight reduction and simplifying the transmission to a single shifter, frame designers needed it to go away to progress the long-travel trail bike. The changer occupied the space they needed to fit aggressive tires on 29-inch wheels and to accommodate those wheels into an area already cramped by short chainstays. SRAM was ready, riders were ready, bike designers were ready, but the bike industry was not ready to ditch the front derailleur.

Stodgy executives (the ones who place orders and write checks) body-blocked the concept. Reportedly, key European brands flat out refused to purchase any drivetrain with a chainring smaller than 40 teeth. However well meaning, these are the dweebs who grew up on road bikes, pushing 54 x 48 tooth cranksets, who speak about Frank Berto in hushed tones, and sneak out 30 minutes early to ensure they'll be properly warmed up for the lunch ride. Challenge these Cosa Nostras of cycling with a new drivetrain concept and they'll pull out their abacus to argue proper gearing steps before tracing crossed lines on a tattered sanskrit papyrus to chart their constellation of shift selections, then they'll proclaim the danger of the satanic cross-over gears.

Accelerated by the fact that we'd prefer a dropper lever on the left side of the handlebar, riders quickly warmed up to XX1's reduced gear selection and visually smaller chainring. Within two years, the front derailleur was scratching for its life, with Shimano crying at its bedside. The Japanese giant redoubled its efforts to convey the enormity of our mistake and comically, bike makers (even vanguard brands who pretended to be all for 1x drivetrains) hedged their bets by continuing to design for front derailleurs in the bottom bracket region of their frames. It took until the end of the decade before frame designers were given the OK to straighten out the S-turn in the right chainstay, put the seat tube back in the middle, spread the swingarm bearings apart and widen the space for the rear tire. The front changer had to endure eight years of hospice before it was mercifully euthanized.

The Dropper Decade

Dropper posts predated 2010, but not as essential original equipment on mountain bikes. The new must-have for the trail riding experience earned its place on this list because it took nearly a decade to debug this simple mechanism. Most early droppers had some fatal flaw or limitation that owners learned to live with, so when RockShox burst onto the scene in 2010 with its hydraulically actuated Reverb, most believed that the savior had arrived. Fate, however, had other plans.

Reverbs developed a habit of sucking air into the oil column that was responsible for freezing the post in your desired location. Oil is incompressible. Air is not, so you can imagine the frustration when Reverbs occasionally became suspension seatposts. While RockShox struggled to engineer a permanent solution. a host of rivals made their appearance with outcomes that ranged from disastrous (Crankbrothers Kronolog) to pretty darn good (KS LEV). Reliability, however, was as spotty as suspension products were in the 1990s, with the possible exception of the mechanically-actuated Fox DOSS which, at 650 grams, could be used as a weapon to fend off rutting moose or grizzly bears.

The first RockShox Reverb debuted in 2010.

After the big names fell short, boutique component makers stepped up to the plate with better results (Revive and OneUp come to mind), but it was Fox who stomped out the fire with the debut of their Transfer post, which earned a reputation as one of the most reliable droppers ever and the most preferred.

RockShox rallied back as the decade came to a close. First, with a redesigned Rerverb, followed by an impressive wireless-electronic version that is already earning high marks.

Fox's Transfer post was the light at the end of the decade's dark tunnel of droppers.

Fat bikes went mainstream: Norco's Ithaqua was one of many fielded by popular brands. Pat Mulrooney photo

Anti-Tech

Too much of a good thing can be poisonous. Imagine what the sport's newest members faced as the decade took shape. Everywhere you looked there was a technical controversy raging: wheel diameters, dropper designs, drivetrains, suspension patents, frame materials, handlebar widths and axle standards... That's a lot of decisions to make for someone who just wanted to ride a bike in the woods. Heck, it's a lot for a seasoned rider who may have been on the hunt to replace his or her aging Ellsworth Truth. The backlash spawned a low-tech revolution.

The vibe was, "If you're not serious about racing, who cares about a few extra pounds or the drag penalty of big tires, as long as we're having fun?" Hardtails returned to popularity. Cult manufactures like Chromag and Surly were booming. Garage builders were popping up everywhere, especially in the UK, blending old-school steel and titanium with new school concepts.

By 2013, fat bikes had become mainstream enough to crowd cross country-skiers for access to groomed trails and sanctioned National Championships would soon follow. Lessons learned from fat bikes

Pipedream's Moxie epitomizes the British new-school hardtail with steel pipes and SAF numbers.

encouraged conventional bike makers to experiment with wider rims and higher volume tires. The plus bike enjoyed a brief zenith before its assets were reincarnated in more robust forms and adopted by aggressive trail riders.

Funny then, that the anti-tech movement would spawn new ideas that would ultimately transform the cutting edge of the sport. Wider rims, high-volume 2.5 and 2.6" tires, and crazy slack geometry came from creative minds who were once marginalized by the direction the sport had taken as it rushed towards 2020 and the kingdom of Enduro Bro.

Wide Rims

Mountain bike wheels in 2010 typically sported rims that were 26 millimeters wide, measured from the outside of the flanges. Wide rims, the kind that you'd special order for your DH bike, measured 28 millimeters outside to outside, with inner widths hovering around 23. The tubeless tire revolution was already in full swing and it was becoming apparent that narrow rims were the root of a number of evils that tubeless users faced.

Syntace pioneered wide-format lightweight rim design back in 2012. The mid-sized MX 35 was considered outrageous, with an inner width of 28.4 millimeters. Syntace photo

Simple as it may seem, Derby and Syntace offered up a solution: widening the stance of the tire. Derby's 30-millimeter inner width carbon rims were laughably huge in 2012. Syntace offered aluminum rims with inner widths up to 34 millimeters. The concept, simple as it was, handily solved the major issues attributed to tubeless: poor lateral stiffness, burping air, and difficulties with mounting and sealing tires. Wide rims also broke ground for future tire improvements, like altering the aspect ratio of height and width to accentuate cornering grip while enhancing straight-line rolling speed.

Old habits fight to the grave and initially, wide rims were not embraced by elite riders - still aren't in some quarters - but greater forces were at play. Aggressive trail riders learned that lower pressure, higher-volume tires generated more grip and by 2019, 30-millimeter inner-width rims became the minimum standard. Tires designed for that rim width are readily available, and the fact that naysayers in the racing community are presently arguing that a 28-millimeter inner-width is wide enough underscores how far we have come.

Ray Scruggs founded Derby rims in 2012, because he couldn't convince rim makers to build wide rims for trail bikes. They look normal now. Derby photo

Flat Pedals Only Won Sam Hill Medals

The Australian who coined the phrase, "Flat pedals win medals," certainly lived up to it, but nobody else did. Sam Hill began the decade with a gold medal at the Mount Sainte Anne Downhill World Championships in 2010, which topped off his career as a DH pro. In spite of commentator Rob Warner's cheerleading, only Gee Atherton, who opted for flats and borrowed shoes from a fan at the 2014 Cairns DH World Cup, would win a World Cup Downhill on flat pedals for the remainder of the decade. "Clipped in for the win" is the new reality for pro downhill competitors, but there may be a glimmer of hope for enduro.

Sam Hill won the overall title in his first full season of EWS competition on flat pedals, then three-peated, winning three consecutive titles to close out a decade that should leave his rivals in awe for years to come. It is doubtful that anyone will come forth from the dwindling crowd of flat pedal pros who will dominate downhill or enduro racing in the future, but Sam Hill has proven - without a doubt - that it could happen. Air-Volume Spacers

Laugh if you want, but it took 20 years of air-sprung suspension development to figure out that a inserting measured plastic spacer into the air chamber could fine-tune its spring rate. Fox offered an air volume spacer kit for their Float RP23 shock in 2011, but the concept fell on deaf ears until wheel travel passed the 150-millimeter mark. Suddenly everyone was talking about small-bump compliance vs big hit bottom-out resistance. RockShox revisited the concept in 2014 with their "Bottomless Token" fork-spring spacer - and it took off.

Air springs may be easily adjusted with a hand pump, but only if you are tuning for one side of the spectrum. Before volume spacers became common, riders had two choices: pressurize your fork or shock until it didn't bottom, at the expense of a harsh ride in the first part of the stroke; or suffer the opposite - a supple ride off the initial stroke, with a tendency to bottom out.

After the Token became suspension currency, with the simplest of tools, riders could modify their spring curves to achieve satisfactory spring pressures at

Volume spacers are attached to the underside of the fork's top cap and either snap or screw together.

Air volume spacers for most shocks can be added inside the air-spring canister.

both initial and full compression. The performance improvement is night and day for some. Fork- and shock-spring volume spacers are included (ask for them) with many new bikes and most every suspension purchase.

Jesse Melamed is no stranger to forest stages. Zermat EWS

The Enduro Effect

For a brief moment, EWS racing appeared to be where the world's trail riders would finally be given a competition format to showcase their skill-sets, their aggressive single-crown dual suspension machines, and preference for natural terrain. Add to that the fact that Strava had already divided local trail centers into segmented race courses and one can understand how enduro captured the imaginations of the sport's wannabe racers.

Of course that didn't happen. EWS racing was hijacked, first by ageing World Cup DH champions, and then by a larger body of gravity experienced pros who saw the enduro format as a second chance to move up the ladder to a podium spot. Within two years, the EWS, like its downhill and cross-country counterparts, distilled into a 100-rider travelling circus of paid professionals and hopeful hangers on - but that was inevitable. This story is about but the profound effect that enduro racing had upon the evolution of the trail bike.

DH has heavily influenced the EWS, and in turn, enduro has had a profound effect upon the basic trail bike.

Mountain bikes, even downhill racing bikes, evolved from cross country. Somewhere around the Intense M1, though, downhill split off and evolved into a gravity powered machine that couldn't be pedaled uphill, but let's forget about that for a second. Sadly, the trail bike's development was tied to its cross-country origins, so its performance was measured as such. Every gram counted, every pedal stroke measured for efficiency, and worse, its geometry had to facilitate arduous climbing. No surprise then that it took over 20 years for the trail bike's head tube angle to progress from 71 to 68 degrees, stem lengths to retract from 130 millimeters to 50, and suspension travel to squeeze out to 130 millimeters. Trail bikes were essentially cross-country designs grudgingly modified to go downhill. That's where we were in 2012.

2020 Santa Cruz Hightower

The near-instant assimilation of enduro by the downhill community reversed that equation. Enduro bikes (true enduro bikes) were downhill machines, modified to go uphill. Somewhere around the middle of this decade, the trailbike got a little too close and was magnetized by enduro. Boom! Permanently severed from its laborious XC evolution and spliced to the DH genome, it was free to adopt once-forbidden gravity-specific attributes. The do-it-all mountain bike was completely transformed in the latter half of the decade. The timid adventurist became a master of its environment. Enduro may have temporarily stolen the trail bike, but it returned it in much better shape.

Batteries on Bikes

Lapierre ei: Lapierre debuted "ei," an electronically controlled RockShox damper that was triggered by an accelerometer on the fork in 2012. The system registered impacts at the fork, then combined information from the cranks to determine whether the rider was pedaling or coasting, and adjusted the compression damping of the shock accordingly. All this occurred before the rear wheel contacted that same bump. Ei captured our attention, but didn't move the needle in the marketplace.

Lapierre collaborated with RockShox to develop a servo motor that operated the Monarch RT3's low-speed compression circuit.

Shimano Di2: Shimano opened up the can of worms with the much anticipated debut of Di2 XTR. Encouraged by the success of its electronic-shifting Dura-Ace and Ultegra Di2 ensembles among its road customers, Shimano set its sights on elite mountain bike riders and it was released in 2014 for an asking price of $2800 USD. Two years later, Shimano followed with an XT-level version at a more affordable, $1300 MSRP. There was no question that Di2 shifted better than Shimano's mechanical counterparts, a victory by itself, but that wasn't enough sizzle to justify its cost, or to divert attention from SRAM's burgeoning fan base.

DI2 XTR used a single rechargeable battery to run all of its components - an environmentally friendly option that may have cost Shimano in the long run. Colin Meagher photos

Fox Live Valve: Fox followed in Shimano's wake with the release of Live Valve. Fox electronics were much faster than Lapierre's, which allowed Fox Live Valve forks and shocks to react individually to impacts before the tires had compressed enough to activate the suspension. Live Valve's purpose was to enhance pedaling feel and efficiency without degrading suspension performance, and it worked seamlessly in its final form.

Unfortunately, during Live Valve's protracted gestation period, riding styles and bicycles had evolved in a different direction.Live Valve was expensive and bikes already pedaled well enough to lug new-school riders to the top of their next descent. Speed, grip and suspension travel were the new currency.

Live Valve managed to enhance the pedaling feel of the already good Pivot Mach 5.5. Ian Collins photo

Magura Vyron Dropper: Launched in 2016, Magura's wirelessly actuated dropper seatpost could have transformed the genre. The wholesale shift by bike makers to internal cable routing made switching and installing dropper posts a pain in the butt. A wireless post would be a sell-and-forget slam dunk for retailers, and riders could switch out their dropper between bikes in a minute. The lackluster response time of the Vyron, however, took some getting used to and bad press killed the concept before riders had the chance to vote on it. Had Magura held back until that glitch was solved, the dropper post landscape might look much different.

A vision of things to come. Magura's wireless dropper was almost revolutionary. Colin Meagher photos

SRAM AXS: Being late to the party has its advantages, SRAM's AXS is wireless - a fundamental element and skillset the iPhone generation has mastered, and that alone may explain why SRAM's electronic component ensemble apparently has reversed the opinions of a decade of naysayers.

Armed with a basic tool kit, just about anyone can install an AXS derailleur and dropper on their bike in under an hour's time. No worries, no compatibility issues, just remember to charge the batteries. Most of us can handle that.

Rumors floating around suggest that SRAM is working overtime to bring AXS to its more affordable ensembles - but those bombs won't drop until the next decade.

SRAM's decision to go wireless will have ramifications beyond its near-perfect shifting. Faster assembly time for both factories and aftermarket customers are only two. Margus Riga photos

Battery Powered Bikes

Bosch forever altered the course of the sport with its pedal-assist electric motor. If anyone had told us in 2010 that we would be sharing trails with electric powered mountain bikes we would have laughed. If a global power tool maker approached government transportation agencies with a proposal to allow uninsured, unlicensed electric mopeds equal access to bicycle lanes and trails, they would have laughed. Instead, Bosh handed off its pedalec system to bicycle makers and we mowed the lawn for them, lobbying government bureaucracies and convincing the naysayers to make it happen. It was marketing brilliance. There's a book in there somewhere.

The start of the men's 2019 UCI sanctioned eMTB World Championships in Mont Sainte Anne.

The marriage of eMTBs into the mountain bike family brings a new crop of riders to the sport who are not wedded to the nuances of our sacred technology - which offers a new opportunity for meaningful change. Once you add a motor, ethereal improvements derived from things like bladed spokes, directionally compliant rims, Kashima coatings and the molecular makeup of frame materials are not all that important. New-school eMTB customers will no-doubt value more measurable performance enhancements like battery life, power output, wheels that stay true and straight, consistent braking power, tires that don't flat, and pro-performing suspension that doesn't require a professor to tune. Fierce competition to court a less technically minded customer will most likely drive down the prices of those high ticket components too.

The last four items on that list should be the first to bounce back to conventional mountain bikers, many of whom have given up on such improvements. Sometimes, it takes another pair of eyes to see that we've missed something crucial, or enough naivety to restate the need for fixes that were swept under the rug. Mountain bikers did that to road bikes, and I anticipate the same treatment from our electrified in-laws. Once again, however, we are talking about the decade to come. Hindsight, they say, is 2020. We shall see...

An Alternative to Agile Coaching

Introduction

Over the last 6 years the role of Agile Coach has emerged in the IT workforce. I’ve worked as one for the last 5 years and most of my work has been done with Suncorp, a large 16000+ person Australian insurance and banking company. Suncorp is known as a leader in Agile adoption and as an example of how Agile can transform an organisation and help it achieve outstanding results.

When Suncorp called me in, back in 2007, to help them transform their entire IT services organisation of around 2000 personnel to an Agile way of working, it was a daunting challenge. There was no structured curriculum available anywhere in the world that covered all roles and maturity levels. There was no Agile training available for Leaders, Project Managers or Change Managers. We had to build it from scratch and that’s how the Agile Academy was born. There were no experienced qualified Agile Project Managers and the Agile maturity of most teams was very low. Furthermore it was hard to find Agile experts with experience and knowledge at a management level. We therefore had to spread the few Agile experts we found over many projects as Agile Coaches. The Coaches reported to a central Coaching Manager and had a dotted line reporting in to the Manager of the project or team they were coaching. This Coaching model suited the purpose, worked well and we slowly but steadily built up the capability of the entire organisation over the last 5 years. Coaching did serve its purpose and was the only option at that time.

But now extensive, high quality Agile training is available at all levels and for all roles, there are quite a few Agile experts in the industry and the overall of level of Agile maturity is much higher.

So is there a better and faster way of building the Agile capability of an organisation? Is there another way that can complement coaching?

It’s now time, in true Agile fashion, to look critically and constructively at the coaching model and see if there if there is an alternative way of building Agile capability.

Original objectives of the Coaching role

The benefits of Agile are now well established and I don’t intend to go into it those here.. Organisations have come to realise that if they want to increase productivity and deliver value faster, cheaper and better, Agile is a proven way to go. Its core principles of teamwork and collaboration, iterative delivery, flexibility to change, focusing on business value and continuous improvement transform teams and organisations and deliver benefits from day one in terms of faster time to market, reduced cost, increased morale and improved quality.

The key objective of the Agile Coach role was to help with this transformation and lift the Agile capability of every member of the team. The success criteria, defined by the change team and the sponsor, at the start of the transformation journey was the sunset of the coaching role.

Challenges of the Agile coaching role

Looking back, I have found that the Agile Coaching role faces a number of challenges and is therefore suboptimal in its effectiveness.

Lack of skin in the game

Agile Coaches don’t have any delivery responsibility and hence no skin in the game. Their commitment to the success of the project and its deliverable is often not perceived as they tend to be focused on the process only and not the outcomes. Because of the lack of skin in the game a number of Agile Coaches didn’t take a pragmatic approach and sometimes alienated themselves from the team and the outcomes. If the Coaches are spread over too many projects, or are only engaged for short intermittent periods, they are sometimes seen to use the ‘Seagull’ approach where they just fly in, squawk a lot, crap all over the project and fly away. This approach actually increases the resistance to change and defeats the purpose of increasing the Agile capability of the entire team and achieving transformational change.

Perceived as an unnecessary overhead

Projects often say they want an Agile Coach to help them but when asked to pay for the Coach from their project budget they cringe and back out. This is often because they have not factored in the Agile Coach role in their original cost estimate or they see the role as an additional overhead on the project. The value of an Agile Coach is hard to quantify and measure and hence the reluctance to pay for one.

Lack of authority or a clear role in the team

Agile Coaches have very little authority in the team and often report to the Project Manager or Team Leader. They offer suggestions and advice but have no authority to make sure that the team follow the recipe in order to learn the correct approach.

This is why very often we see teams adopting Agile ‘partly’ or selectively. More often than not they go against the advice of the Coach and all the Coach can do is whinge a little and finally just walk away. Furthermore it’s very hard for the Coach to hold any individual in the team accountable for not following a proposed approach or practice. The biggest culprits are sometimes the Leaders or Project Managers, to whom the Coaches report. It’s hard to hold anyone accountable if they are not given suitable responsibility to match.

‘Coaching’ alone is not the ideal model

Unlike Consulting, Coaching involves not giving answers, but asking the right questions so that the person or team can come up with the appropriate answer. In Agile immature teams and teams that are inherently resistant to the change, the adoption of the coaching form of capability building alone, is not appropriate and does not work well. One needs a more consultative, instructive and training oriented approach with teams who are taking their first Agile steps. An Agile Coach has to train, consult and coach based on the situation. However the percentage of true coaching activities is very small, compared to the consulting and training components. When an Agile Coach takes a consulting approach, teams and the Project Managers could get a bit defensive and resistant, as what they asked for is an ‘Agile Coach’ and not a consultant or trainer.

Calibre of Coaches

At a recent Agile Australia conference there was a panel of Agile Coaches talking on the subject and one of the questions from the audience was ‘How many of you have had any formal coaching training’? Only 1 of the 5 had some form of coaching training.

In my years as an Agile Coach I have seen some great Agile practitioners with indepth Agile knowledge and a breath of Agile experience, but only a few who have been trained as an Agile practitioner and as a Coach.

The main criterion for becoming an Agile Coach has been ones knowledge and experience of Agile. The ability to train or coach is seldom taken into account. More recently, with the demand for Agile Coaches increasing as more and more companies try to go Agile, a large number of Agile practitioners, with little or no formal coaching training, certification (International Coaching Federation) or experience, label themselves as “Coaches”.

In the words of Bruce Weir, an Executive General Manager, at Suncorp, “Give me someone who can lead the team in an Agile manner and lift their Agile capability at the same time. I want someone who has skin in the game and can be held accountable with clear measurable goals”. Sandra Arps, the head of a PMO in Suncorp says “I need experienced capable Agile Project and Change Managers. Not Coaches who float in and out and whose value is hard to measure”.

I think the Agile Coaching model did deliver value at a time when the overall maturity was very low and almost no structured training existed, when it was impossible to find experienced Agile Leaders, PM’s or IM’s (Iteration Managers/Scrum Masters). But times have changed and experienced Agile practitioners are now more easily available. I feel that the Agile Coaching model has its drawbacks and is not necessarily the only model or the best model for increasing Agile capability.

So what’s the alternative?

I would hate to ‘do a seagull’ with this article so I hereby put forward an alternative suggestion or solution for the challenge of lifting Agile capability and transforming an organisation to an Agile way of working.

If you look at a Coach of a sports team, they are responsible for the success of the team and not just their capability. If you look at the Lean process or at Six Sigma, the focus is on leaders as teachers and they seldom use external Coaches that don’t have delivery responsibility. The leaders do the coaching as one of their tasks.

We don’t have Java or Prince2 Coaches or Coaches for any of the other key capabilities in the IT industry, so can we learn from their models? Most other capabilities have the practitioners train the other team members and the team while on the job.

I believe an alternative model that could work very well is having trained and experienced Agile Practitioner Managers (APMs) build the capability. These could be Team Leaders, Project Managers, Delivery Managers, Change Managers or Iteration managers (read Scrum Master), in charge of and running the Agile teams and this would deliver the best outcome for the project and the best capability uplift for the whole team.

The APM model avoids all the pitfalls of the current coaching model as listed above.

APMs would have definite skin in the game and be driven to deliver successful projects and outcomes.

There would be a budget to fund them, as they would not be seen as an overhead. Every project has to have a Project Manager and/or an Iteration Manager.

They would have both the responsibility and the authority to push and cajole resistant teams in the right direction, build their capability and be measured and held accountable for it.

The APMs would be best positioned to offer a blended model of learning which combines leadership, consultancy, coaching, mentoring and training where necessary.

I also believe the core capability of these APMs would be the fact that they are first and foremost good leaders and managers and then agile practitioners, as opposed to being an Agile practitioner with marginal real world experience in leadership.

The APM model would address all the pitfalls of the Coaches model and be able to deliver more bang for buck.

Agile has matured and come a long way over the years but it is now time to take it to a new level and build in ways to accelerate the learning curve. What is Agile 2.0 or 3.0? Whatever the answer to this question is, whether it be ‘Continuous Delivery’, ‘Experience Design’, or ‘Product Management’, it is clear that the way capability is built and organisations transformed will also need to adapt to keep up with the changing Agile maturity landscape.

How could you make it happen?

The key challenge is finding or developing APMs. As the Agile way of working is relatively new it’s very difficult to find experienced or even trained Agile Leaders, Practitioner Managers such as Agile Project Managers, Agile Change Managers or even Agile Iteration Managers/Scrum Masters. If an organisation wants to embark on an Agile transformation journey, where do they start? How do they find or develop these APMs to support their Agile transformation program?

Every organisation has a number of Project Managers, Change Managers or Delivery Managers, whether they are contract or in-house staff, who already know the organisation and have the experience in their core management practices. A good place to start would be to corral and intensively train these people to be APMs. Then embed or assign them to the critical projects that are selected for the Agile journey and have one experienced Agile Super Coach (an Agile trainer, or senior Agile Coach) on hand to help them on their Agile journey. This Agile Super Coach can support multiple APMs and provide the hands-on, onthe- job, training they would need to employ the practices they learnt in the classroom. These APMs could be grouped together in a central team or virtual team, and assigned out to projects on request. By being in one central team the APMs could increase their Agile capability and share and learn from each others in a more efficient manner. The projects would be willing to fund these APMs because they would have budgeted for a PM or IM anyway and won’t see it as an overhead.

It is also a good idea to train all the organisational Leaders (Line and Executive Managers) as well as the APMs so that they can support and steer the APMs in an Agile manner.

Summary

In summary, I feel that a good blended learning programme, both online, class room based and on-the-job, for Agile Practitioner Managers, followed by the spread of these managers across projects, with support from one Agile Super Coach, would be a very effective model for rolling out Agile as a way of working in an organisation. This APM model could be blended with a normal Coaching model in geographic areas where Agile training and Agile expertise is still not easily available.

The APM model can be more effective in speeding up the Agile maturity of an organisation and can be used in conjunction with the Coaching model if needed. It’s time for Leaders and the Agile Practitioner Managers to coach, as any Leader normally does as part of their job, and grow the Agile capability of the team and the organisation as a whole.

About the Author Phil Abernathy is an inspiring Agile/Lean Leadership speaker, trainer, coach and consultant. His mission is to make every work place a happy place. His passion is making a material difference to the top and bottom lines of companies by substantially lifting the capability of their Leaders. With over 30 years of experience in blue chip companies all over the world, Phil is the owner and founder of Purple Candor, an Australian company focused on enabling leadership excellence.

Phil Abernathy is an inspiring Agile/Lean Leadership speaker, trainer, coach and consultant. His mission is to make every work place a happy place. His passion is making a material difference to the top and bottom lines of companies by substantially lifting the capability of their Leaders. With over 30 years of experience in blue chip companies all over the world, Phil is the owner and founder of Purple Candor, an Australian company focused on enabling leadership excellence.The Existential Question of Whom to Trust

Special Report: An existential question facing humankind is whom can be trusted to describe the world and its conflicts, especially since mainstream experts have surrendered to careerism, writes Robert Parry.

By Robert Parry

The looming threat of World War III, a potential extermination event for the human species, is made more likely because the world’s public can’t count on supposedly objective experts to ascertain and evaluate facts. Instead, careerism is the order of the day among journalists, intelligence analysts and international monitors – meaning that almost no one who might normally be relied on to tell the truth can be trusted.

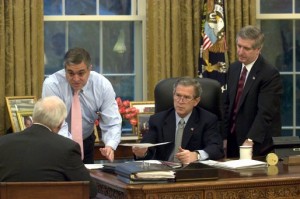

Secretary of State Colin Powell addressed the United Nations on Feb. 5. 2003, citing satellite photos which supposedly proved that Iraq had WMD, but the evidence proved bogus. CIA Director George Tenet is behind Powell to the left.

The dangerous reality is that this careerism, which often is expressed by a smug certainty about whatever the prevailing groupthink is, pervades not just the political world, where lies seem to be the common currency, but also the worlds of journalism, intelligence and international oversight, including United Nations agencies that are often granted greater credibility because they are perceived as less beholden to specific governments but in reality have become deeply corrupted, too.

In other words, many professionals who are counted on for digging out the facts and speaking truth to power have sold themselves to those same powerful interests in order to keep high-paying jobs and to not get tossed out onto the street. Many of these self-aggrandizing professionals – caught up in the many accouterments of success – don’t even seem to recognize how far they’ve drifted from principled professionalism.

A good example was Saturday night’s spectacle of national journalists preening in their tuxedos and gowns at the White House Correspondents Dinner, sporting First Amendment pins as if they were some brave victims of persecution. They seemed oblivious to how removed they are from Middle America and how unlikely any of them would risk their careers by challenging one of the Establishment’s favored groupthinks. Instead, these national journalists take easy shots at President Trump’s buffoonish behavior and his serial falsehoods — and count themselves as endangered heroes for the effort.

Foils for Trump

Ironically, though, these pompous journalists gave Trump what was arguably his best moment in his first 100 days by serving as foils for the President as he traveled to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on Saturday and basked in the adulation of blue-collar Americans who view the mainstream media as just one more appendage of a corrupt ruling elite.

The photograph released by the White House of President Trump meeting with his advisers at his estate in Mar-a-Lago on April 6, 2017, regarding his decision to launch missile strikes against Syria.

Breaking with tradition by snubbing the annual press gala, Trump delighted the Harrisburg crowd by saying: “A large group of Hollywood celebrities and Washington media are consoling each other in a hotel ballroom” and adding: “I could not possibly be more thrilled than to be more than 100 miles away from [the] Washington swamp … with much, much better people.” The crowd booed references to the elites and cheered Trump’s choice to be with the common folk.

Trump’s rejection of the dinner and his frequent criticism of the mainstream media brought a defensive response from Jeff Mason, president of the White House Correspondents’ Association, who complained: “We are not fake news. We are not failing news organizations. And we are not the enemy of the American people.” That brought the black-tie-and-gown gathering to its feet in a standing ovation.

Perhaps the assembled media elite had forgotten that it was the mainstream U.S. media – particularly The Washington Post and The New York Times – that popularized the phrase “fake news” and directed it blunderbuss-style not only at the few Web sites that intentionally invent stories to increase their clicks but at independent-minded journalism outlets that have dared question the elite’s groupthinks on issues of war, peace and globalization.

The Black List

Professional journalistic skepticism toward official claims by the U.S. government — what you should expect from reporters — became conflated with “fake news.” The Post even gave front-page attention to an anonymous group called PropOrNot that published a black list of 200 Internet sites, including Consortiumnews.com and other independent-minded journalism sites, to be shunned.

The Washington Post building in downtown Washington, D.C. (Photo credit: Washington Post)

But the mainstream media stars didn’t like it when Trump began throwing the “fake news” slur back at them. Thus, the First Amendment lapel pins and the standing ovation for Jeff Mason’s repudiation of the “fake news” label.

Yet, as the glitzy White House Correspondents Dinner demonstrated, mainstream journalists get the goodies of prestige and money while the real truth-tellers are almost always outspent, outgunned and cast out of the mainstream. Indeed, this dwindling band of honest people who are both knowledgeable and in position to expose unpleasant truths is often under mainstream attack, sometimes for unrelated personal failings and other times just for rubbing the powers-that-be the wrong way.

Perhaps, the clearest case study of this up-is-down rewards-and-punishments reality was the Iraq War’s WMD rationale. Nearly across the board, the American political/media system – from U.S. intelligence analysts to the deliberative body of the U.S. Senate to the major U.S. news organizations – failed to ascertain the truth and indeed actively helped disseminate the falsehoods about Iraq hiding WMDs and even suggested nuclear weapons development. (Arguably, the “most trusted” U.S. government official at the time, Secretary of State Colin Powell, played a key role in selling the false allegations as “truth.”)

Not only did the supposed American “gold standard” for assessing information – the U.S. political, media and intelligence structure – fail miserably in the face of fraudulent claims often from self-interested Iraqi opposition figures and their neoconservative American backers, but there was minimal accountability afterwards for the “professionals” who failed to protect the public from lies and deceptions.

Profiting from Failure

Indeed, many of the main culprits remain “respected” members of the journalistic establishment. For instance, The New York Times’ Pentagon correspondent Michael R. Gordon, who was the lead writer on the infamous “aluminum tubes for nuclear centrifuges” story which got the ball rolling for the Bush administration’s rollout of its invade-Iraq advertising campaign in September 2002, still covers national security for the Times – and still serves as a conveyor belt for U.S. government propaganda.

New York Times building in New York City. (Photo from Wikipedia)

The Washington Post’s editorial page editor Fred Hiatt, who repeatedly informed the Post’s readers that Iraq’s secret possession of WMD was a “flat-fact,” is still the Post’s editorial page editor, one of the most influential positions in American journalism.

Hiatt’s editorial page led a years-long assault on the character of former U.S. Ambassador Joseph Wilson for the offense of debunking one of President George W. Bush’s claims about Iraq seeking yellowcake uranium from Niger. Wilson had alerted the CIA to the bogus claim before the invasion of Iraq and went public with the news afterwards, but the Post treated Wilson as the real culprit, dismissing him as “a blowhard” and trivializing the Bush administration’s destruction of his wife’s CIA career by outing her (Valerie Plame) in order to discredit Wilson’s Niger investigation.

At the end of the Post’s savaging of Wilson’s reputation and in the wake of the newspaper’s accessory role in destroying Plame’s career, Wilson and Plame decamped from Washington to New Mexico. Meanwhile, Hiatt never suffered a whit – and remains a “respected” Washington media figure to this day.

Careerist Lesson

The lesson that any careerist would draw from the Iraq case is that there is almost no downside risk in running with the pack on a national security issue. Even if you’re horrifically wrong — even if you contribute to the deaths of some 4,500 U.S. soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis — your paycheck is almost surely safe.

President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney receive an Oval Office briefing from CIA Director George Tenet. Also present is Chief of Staff Andy Card (on right). (White House photo)

The same holds true if you work for an international agency that is responsible for monitoring issues like chemical weapons. Again, the Iraq example offers a good case study. In April 2002, as President Bush was clearing away the few obstacles to his Iraq invasion plans, Jose Mauricio Bustani, the head of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons [OPCW], sought to persuade Iraq to join the Chemical Weapons Convention so inspectors could verify Iraq’s claims that it had destroyed its stockpiles.

The Bush administration called that idea an “ill-considered initiative” – after all, it could have stripped away the preferred propaganda rationale for the invasion if the OPCW verified that Iraq had destroyed its chemical weapons. So, Bush’s Undersecretary of State for Arms Control John Bolton, a neocon advocate for the invasion of Iraq, pushed to have Bustani deposed. The Bush administration threatened to withhold dues to the OPCW if Bustani, a Brazilian diplomat, remained.

It now appears obvious that Bush and Bolton viewed Bustani’s real offense as interfering with their invasion scheme, but Bustani was ultimately taken down over accusations of mismanagement, although he was only a year into a new five-year term after having been reelected unanimously. The OPCW member states chose to sacrifice Bustani to save the organization from the loss of U.S. funds, but – in so doing – they compromised its integrity, making it just another agency that would bend to big-power pressure.

“By dismissing me,” Bustani said, “an international precedent will have been established whereby any duly elected head of any international organization would at any point during his or her tenure remain vulnerable to the whims of one or a few major contributors.” He added that if the United States succeeded in removing him, “genuine multilateralism” would succumb to “unilateralism in a multilateral disguise.”

The Iran Nuclear Scam

Something similar happened regarding the International Atomic Energy Agency in 2009 when Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the neocons were lusting for another confrontation with Iran over its alleged plans to build a nuclear bomb.

Yukiya Amano, a Japanese diplomat and director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

According to U.S. embassy cables from Vienna, Austria, the site of IAEA’s headquarters, American diplomats in 2009 were cheering the prospect that Japanese diplomat Yukiya Amano would advance U.S. interests in ways that outgoing IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei wouldn’t; Amano credited his election to U.S. government support; Amano signaled he would side with the United States in its confrontation with Iran; and he stuck out his hand for more U.S. money.

In a July 9, 2009, cable, American chargé Geoffrey Pyatt said Amano was thankful for U.S. support of his election. “Amano attributed his election to support from the U.S., Australia and France, and cited U.S. intervention with Argentina as particularly decisive,” the cable said.

The appreciative Amano informed Pyatt that as IAEA director-general, he would take a different “approach on Iran from that of ElBaradei” and he “saw his primary role as implementing safeguards and UNSC [United Nations Security Council] Board resolutions,” i.e. U.S.-driven sanctions and demands against Iran.

Amano also discussed how to restructure the senior ranks of the IAEA, including elimination of one top official and the retention of another. “We wholly agree with Amano’s assessment of these two advisors and see these decisions as positive first signs,” Pyatt commented.

In return, Pyatt made clear that Amano could expect strong U.S. financial assistance, stating that “the United States would do everything possible to support his successful tenure as Director General and, to that end, anticipated that continued U.S. voluntary contributions to the IAEA would be forthcoming. Amano offered that a ‘reasonable increase’ in the regular budget would be helpful.”

What Pyatt made clear in his cable was that one IAEA official who was not onboard with U.S. demands had been fired while another who was onboard kept his job.

Pandering to Israel

Pyatt learned, too, that Amano had consulted with Israeli Ambassador Israel Michaeli “immediately after his appointment” and that Michaeli “was fully confident of the priority Amano accords verification issues.” Michaeli added that he discounted some of Amano’s public remarks about there being “no evidence of Iran pursuing a nuclear weapons capability” as just words that Amano felt he had to say “to persuade those who did not support him about his ‘impartiality.’”

U.S. Army Pvt. Chelsea (formerly Bradley) Manning.

In private, Amano agreed to “consultations” with the head of the Israeli Atomic Energy Commission, Pyatt reported. (It is ironic indeed that Amano would have secret contacts with Israeli officials about Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program, which never yielded a single bomb, when Israel possesses a large and undeclared nuclear arsenal.)

In a subsequent cable dated Oct. 16, 2009, the U.S. mission in Vienna said Amano “took pains to emphasize his support for U.S. strategic objectives for the Agency. Amano reminded ambassador [Glyn Davies] on several occasions that he was solidly in the U.S. court on every key strategic decision, from high-level personnel appointments to the handling of Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program.

“More candidly, Amano noted the importance of maintaining a certain ‘constructive ambiguity’ about his plans, at least until he took over for DG ElBaradei in December” 2009.

In other words, Amano was a bureaucrat eager to bend in directions favored by the United States and Israel regarding Iran’s nuclear program. Amano’s behavior surely contrasted with how the more independent-minded ElBaradei resisted some of Bush’s key claims about Iraq’s supposed nuclear weapons program, correctly denouncing some documents as forgeries.

The world’s public got its insight into the Amano scam only because the U.S. embassy cables were among those given to WikiLeaks by Pvt. Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning, for which Manning received a 35-year prison sentence (which was finally commuted by President Obama before leaving office, with Manning now scheduled to be released in May – having served nearly seven years in prison).

It also is significant that Geoffrey Pyatt was rewarded for his work lining up the IAEA behind the anti-Iranian propaganda campaign by being made U.S. ambassador to Ukraine where he helped engineer the Feb. 22, 2014 coup that overthrew elected President Viktor Yanukovych. Pyatt was on the infamous “fuck the E.U.” call with U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs Victoria Nuland weeks before the coup as Nuland handpicked Ukraine’s new leaders and Pyatt pondered how “to midwife this thing.”

Rewards and Punishments

The existing rewards-and-punishments system, which punishes truth-tellers and rewards those who deceive the public, has left behind a thoroughly corrupted information structure in the United States and in the West, in general.

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko shakes hands with U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt as U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry shakes hands with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin in Kiev, Ukraine, on July 7, 2016.[State Department Photo)

Across the mainstream of politics and media, there are no longer the checks and balances that have protected democracy for generations. Those safeguards have been washed away by the flood of careerism.

The situation is made even more dangerous because there also exists a rapidly expanding cadre of skilled propagandists and psychological operations practitioners, sometimes operating under the umbrella of “strategic communications.” Under trendy theories of “smart power,” information has become simply another weapon in the geopolitical arsenal, with “strategic communications” sometimes praised as the preferable option to “hard power,” i.e. military force.

The thinking goes that if the United States can overthrow a troublesome government by exploiting media/propaganda assets, deploying trained activists and spreading selective stories about “corruption” or other misconduct, isn’t that better than sending in the Marines?

While that argument has the superficial appeal of humanitarianism – i.e., the avoidance of armed conflict – it ignores the corrosiveness of lies and smears, hollowing out the foundations of democracy, a structure that rests ultimately on an informed electorate. Plus, the clever use of propaganda to oust disfavored governments often leads to violence and war, as we have seen in targeted countries, such as Iraq, Syria and Ukraine.

Wider War

Regional conflicts also carry the risk of wider war, a danger compounded by the fact that the American public is fed a steady diet of dubious narratives designed to rile up the population and to give politicians an incentive to “do something.” Since these American narratives often deviate far from a reality that is well known to the people in the targeted countries, the contrasting storylines make the finding of common ground almost impossible.

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

If, for instance, you buy into the Western narrative that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad gleefully gases “beautiful babies,” you would tend to support the “regime change” plans of the neoconservatives and liberal interventionists. If, however, you reject that mainstream narrative – and believe that Al Qaeda and its friendly regional powers may be staging chemical attacks to bring the U.S. military in on their “regime change” project – you might favor a political settlement that leaves Assad’s fate to the later judgment of the Syrian people.

Similarly, if you accept the West’s storyline about Russia invading Ukraine and subjugating the people of Crimea by force – while also shooting down Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 for no particular reason – you might support aggressive countermoves against “Russian aggression,” even if that means risking nuclear war.

If, on the other hand, you know about the Nuland-Pyatt scheme for ousting Ukraine’s elected president in 2014 and realize that much of the other anti-Russian narrative is propaganda or disinformation – and that MH-17 might well have been shot down by some element of Ukrainian government forces and then blamed on the Russians [see here and here] – you might look for ways to avoid a new and dangerous Cold War.

Who to Trust?

But the question is: whom to trust? And this is no longer some rhetorical or philosophical point about whether one can ever know the complete truth. It is now a very practical question of life or death, not just for us as individuals but as a species and as a planet.

Illustration by Chesley Bonestell of nuclear bombs detonating over New York City, entitled “Hiroshima U.S.A.” Colliers, Aug. 5, 1950.

The existential issue before us is whether – blinded by propaganda and disinformation – we will stumble into a nuclear conflict between superpowers that could exterminate all life on earth or perhaps leave behind a radiated hulk of a planet suitable only for cockroaches and other hardy life forms.

You might think that with the stakes so high, the people in positions to head off such a catastrophe would behave more responsibly and professionally. But then there are events like Saturday night’s White House Correspondents Dinner with self-important media stars puffing about with their First Amendment pins. And there’s President Trump’s realization that by launching missiles and talking tough he can buy himself some political space from the Establishment (even as he sells out average Americans and kills some innocent foreigners). Those realities show that seriousness is the farthest thing from the minds of Washington’s insiders.

It’s just too much fun – and too profitable in the short-term – to keep playing the game and hauling in the goodies. If and when the mushroom clouds appear, these careerists can turn to the cameras and blame someone else.

Investigative reporter Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. You can buy his latest book, America’s Stolen Narrative, either in print here or as an e-book (from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com).

Comments

Post a Comment