High Times Greats: Interview With Susan Sontag, The Dark Lady Of Pop Philosophy

Susan Sontag (1933 – 2004) would have been 87 on January 16. To celebrate, we’re republishing a rare interview with her from the March, 1978 edition of High Times, conducted by Victor Bockris.

Among American intellectuals, Susan Sontag is probably the only Harvard-educated philosopher who digs punk rock. Sontag became famous in the Sixties when her series of brilliant essays on politics, pornography and art, including the notorious “Notes on Camps,” were collected in Against Interpretation—a book that defended the intuitive acceptance of art against the superficial, cerebral apprehension of it, then fashionable among a small hand of extremely powerful, rigid intellectuals who, for example, dismissed such American classics as Naked Lunch, Howl, On the Road, Andy Warhol’s film Chelsea Girls, etc., as trash. With the impact of her concise arguments, Sontag was immediately labeled the Queen of the Aesthetes, the philosophical champion of pop art and rock and roll.

Since then she has written many more essays, a second novel, edited the works of Antonin Artaud (founder of the Theater of Cruelty and an early mescaline user), made two films and undergone radical surgery and two years of chemotherapy for a rare and advanced form of cancer. Thus Susan Sontag continues to live on the edge of life and death, an unusual address for an intellectual essayist but essential for anyone who aspires, as she does, to tell the truth about the present.

Her first book in seven years, On Photography, was greeted this winter with the familiar violent controversy. Most reviewers treated it as an uncompromising attack on photography itself—everything from photojournalism to baby pictures— and a complete desertion of her Sixties art-for-art’s-sake position for the lofty ground of analytical moralism. As Sontag makes clear for the first time in this interview, On Photography is not about photography at all, but the way it is put to use by the American system. Thus On Photography remains true to Sontag’s main idea of her task as a writer: to examine the majority opinion and expose it from the opposite point of view, putting emphasis on her “responsibility to the truth.” The method has proved explosive.

Sontag decided to give us an interview instead of attending a Ramones gig at CBGB’s because she thought it would be fun. She spoke intriguingly for hours about famous dopers she’d known (Jean Paul Sartre, a surprise lifelong speed freak, among them), grass, booze, punk rock, art, the Sixties and—always—truth.

High Times: I’ve been told that you don’t give very many interviews.

Sontag: No, I don’t. Sure.

High Times: Why are you giving this one to High Times?

Sontag: Well, I’m giving this one because I haven’t published a proper book in seven years. I’m giving an interview because… because it’s High Times. I was intrigued by that, sure. I thought, well, that’s odd. I hadn’t thought of that. And also because I’m going away, so it’s a little bit hit-and-run. And I suppose in a way I have been hiding.

There is a crisis you go through after a certain amount of work. Some people say after a decade, but when you’ve done a lot of work and you hear a lot about it and discover that it really does exist out there—you can call it being famous—then you think, well, is it any good? And, what do I want to go on doing? And, of course, you can’t shut out people’s reactions, and to a certain extent you do get labeled, and I hate that.

I find now that I am being described as somebody who has moved away from the positions or ideas that I advocated in the Sixties, as if I’ve reneged. I just got tired of hearing my ideas in other people’s mouths. If some of the things that I said stupidly or accurately in the Sixties, which were then minority positions, have become positions that are much more common, well, then again I would like to say something else.

High Times: Do you feel you have any responsibility for the effect of what you have to say on other people?

Sontag: No, I feel I have a responsibility to the truth. I’m not going to say something that I don’t think is true, and I think the truth is always valuable. If the truth makes people uncomfortable or is disturbing, that seems to me a good thing.

I suppose unconsciously I’m always making an estimate when I’m starting some kind of project of what people think. And then I say, well, given that people think this, what can be said in addition to this or what can be said in contradiction to that? There’s always some sense of where people are, so I do in a way think of my essay writing as adversary writing. The selection of subjects doesn’t necessarily represent my most important taste or interests; it has to do with the sense of what’s being neglected or what’s being viewed in a way that seems to exclude other things which are true.

But I find myself absolutely baffled by the question of the effect or influence of what one is doing. If I think of my own work and I question what effect it is having, I have to throw up my hands.

Beyond these baby statements like “I want to tell the truth” or “I want to write well,” I really don’t know. It’s not only that I don’t know, I don’t know how I would know, I don’t know what I would do with it. I’m always amazed at writers who say, “I want to be the conscience of my generation. I want to say the things that’ll change what people feel or think.” I don’t know what that means.

High Times: Do you think that the Sixties concept of a new consciousness changing things is rather lightweight?

Sontag: Yes. In a word.

High Times: And yet, drugs are now more a part of our society than they were in the Sixties.

Sontag: Absolutely. There was an article in the New York Times the other day about people smoking pot in public in the major cities, and that being absolutely accepted. That’s a major change. I have a friend who spent three years in jail in Texas for having two joints in his pocket. As he crossed from Mexico into Texas he was arrested by the border police. So these changes are important.

High Times: Do you have any feelings about an increasingly widespread use of drugs?

Sontag: I think marijuana is much better than liquor. I think a society which is addicted to a very destructive and unhealthy drug, namely alcohol, certainly has no right to complain or be sanctimonious or censor the use of a drug which is much less harmful.

If one leaves it on the level of soft drugs, I think the soft drugs are much less harmful. They’re much better and more pleasurable and physically less dangerous than alcohol. And above all, less addictive. So as far as that goes, I think fine. What bothers me is that a lot of people are drifting back to alcohol. What I rather liked in the Sixties about the drug use was the repudiation of alcohol. That was very healthy. And now alcohol has come back.

High Times: Do you think drugs encourage consumers?

Sontag: What I prefer about soft drugs as opposed to alcohol is that it seems to be more pleasurable; maybe it just has to do with my experience. I’m not terribly interested in soft drugs, but I certainly would prefer a joint to a whiskey any day. I think that I rather like the fact that soft drugs tend to make people a little lazier, and they don’t, at least in my experience, encourage aggressive or violent impulses. Of course if you’ve got them, nothing’s going to stop you from acting them out.

But I don’t feel that drugs are any more connected with consumerism. It’s just a historical phenomenon that the drug culture became widespread at a moment when the consumer society was more developed. And, on the contrary, in North Africa, in Morocco, which is a country that I know pretty well, the new thing for the past 20 years among the younger, more Westernized Moroccans is alcohol. They think of hashish as the drug of their parents, their parents being lazy and not interested in consumption and getting ahead and modernizing the country. So the young doctors and lawyers and movers and groovers in Moroccan society tend to prefer alcohol.

High Times: I think it’s interesting that in this society we take drugs a lot, and in other societies they don’t take drugs at all. What’s the difference?

Sontag: I think what interests me now, the little I know about it, is that this is now becoming a mature drug society, in relation to, let’s say, Western Europe. This is because we have enough time that people have been taking drugs in different strata of the society; that we’re getting different kinds of drug cultures and even a kind of naturalization of the drug thing; that it’s not a big deal. Whereas in a country like France or Italy, which I know pretty well, they’re about where we were ten years ago. It’s still a kind of spooky thing, it’s a daring thing, it’s a thing that people use in a rather violent or self-destructive way.

High Times: Do you do any of your writing on grass?

Sontag: I’ve tried, but I find it too relaxing. I use speed to write, which is the opposite of grass. Sometimes when I’m really stuck I will take a very mild form of speed to get going again.

High Times: What does it do?

Sontag: It eliminates the need to eat, sleep or pee or talk to other people. And one can really sit 20 hours in a room and not feel lonely or tired or bored. It gives you terrific powers of concentration. It also makes you loquacious. So if I do any writing on speed, I try to limit it.

First of all, I take very little at a time, and then I try to actually limit it as far as the amount of time that I’ll be working on a given thing on that kind of drug. So that most of the time my mind will be clear, and I can edit down what has perhaps been too easily forthcoming. It makes you a little uncritical and a little too easily satisfied with what you’re doing. But sometimes when you’re stuck it’s very helpful.

I think more writers have worked on speed than have worked on grass. Sartre, for instance, has been on speed all his life, and it really shows. Those endlessly long books are obviously written on speed, a book like Saint Genet. He was asked by Gallimard to write a preface to the collected works of Genet. They decided to bring it out in a series of uniform volumes, and they asked him to write a 50-page preface. He wrote an 800-page book. It’s obviously speed writing. Malraux used to write on speed. You have to be careful. I think one of the interesting things about the nineteenth century is it seems like they had natural speed. Somebody like Balzac…or a Dickens.

High Times: They must have had something. Perhaps it was alcohol.

Sontag: Well, you know in the nineteenth century a lot of people took opium, which was available in practically any pharmacy as a painkiller.

High Times: Would opium be good to write on?

Sontag: I don’t know, but an awful lot of nineteenth-century writers were addicted to opiates of one kind or another.

High Times: Is that an interesting concept, the relationship between writers and drugs?

Sontag: I don’t think so. I don’t think anything comes out that you haven’t gotten already.

High Times: Then why is there this long history of writers and stimulants?

Sontag: I think it’s because it’s not natural for people to be alone. I think that there is something basically unnatural about writing in a room by yourself, and that it’s quite natural that writers and also painters need something to get through all those hours and hours and hours of being by yourself, digging inside your own intestines. I think it’s probably a defense against anxiety that so many writers have been involved in drugs. It’s true that they have, and whole generations of writers have been alcoholics.

High Times: Is it possible to say what it is that makes someone want to write?

Sontag: I think for me it’s first of all an admiration of other writers. That’s probably the greatest single motivation that I have had. I’ve been so overcome by admiration for a number of writers that I wanted to join that army. And even if I thought that I was just going to be a foot soldier in that army and never one of the captains or majors or generals, I still wanted to do that thing which I admired so intensely. But if I’d never read so many books that I really loved, I’m sure I would not have wanted to be a writer.

High Times: You recently said that artists should be less devoted to creating new forms of hallucination and more devoted to piercing through the hallucinations that nowadays pass for reality. Do you think artists have a responsibility to arrest decay?

Sontag: Artists are no different than anybody else. They are first of all creatures of the society that they live in. I think one of the great illusions that people had—and that I shared to a certain extent—was that modern art could be in some kind of permanent adversary, critical relationship to the culture. But I can just see more and more of a fit between the values of modern art and the values of a consumer society.

I don’t think any of this can be described in the simple way people used to do in the Sixties, talking about being co-opted. It’s a much more organic relationship. It’s not that things start out being critical and get taken up by the establishment. It’s that the values in a great deal of avant-garde or modern art are values that fit perfectly well in a consumer society, where everyone’s supposed to have pluralistic taste and standards are subjective and people really don’t care about the truth.

High Times: Do you see punk as a moral movement?

Sontag: I really don’t know how to answer that. One is so suspicious of what one’s reactions might be because one is ten years older. I remember when I first heard the Rolling Stones. When I went to their very first concert in New York at the Academy of Music, I was absolutely thrilled. But I was ten or twelve years younger than I am now. I haven’t gone to any punk rock concerts, but I have some records. And I find in the lyrics something rather different, a kind of despair that I didn’t feel with the Rolling Stones. I mean, I don’t feel offended, I don’t feel outraged, it’s nothing like that, but I feel a sort of bleakness. I agree that the society that is so nihilistic at its core does not deserve a sanctimonious art which simply covers up the inner bleakness of the society, so in that sense, of course I’m not against…

High Times: It releases a lot of energy when someone suddenly puts their finger on the pulse of the time. I know from being in England in ’62 when the Beatles broke. It simply made everyone feel good.

Sontag: I’d like to believe in the comparison you’re suggesting, and I try to think that way too because I’m horrified by this kind of sanctimonious moralistic reaction to everything, and I remember exactly what you’re describing. I remember saying to myself, to my son and to friends, I’ve never felt so good. I felt a physical energy, a sensual energy, a sexual energy, but above all a feeling in my body…

But you see, I think the Sex Pistols and the other groups would be quite acceptable if they seemed more ironic to people. And I think they are very ironic. But I think they’re not perceived as ironic, and once they are perhaps that will be their form of domestication. Then it will be perfectly all right. You see, listen, I didn’t want to be labeled the Queen of the Aesthetes in the Sixties, and I don’t want to be the Queen of the Moralists in the Seventies. It’s not as simple as that at all.

High Times: I think you’re being forced into that position.

Sontag: Well, I see that now, I see that in everything that I have dared to read about myself that thing comes up. Something that interests me less and less is the narcissism of this society, is the way that people just care about what they’re feeling. And it isn’t that I think there’s something wrong about caring about what you feel, but I think that you have to have some vocabulary or some stretch of the imagination to do it with, and it seems that the means are shrinking.

“How are you feeling?”

“Oh, well, I’m feeling fine. I’m very laid back, er wow, terrific.”

What is being said about feelings is less and less. It’s awfully primitive. You do your thing and I’ll do my thing. That kind of attitude seems very shallow. It seems as if an awful lot of complexity has been lost. If one can keep the debate going between the aesthetic way of looking at things and the moralist way of looking at things, that already gives more structure, more density to the situation.

If I seemed to be championing the aesthete’s way of looking at things it’s because I thought the moralists really did have it all their way at the time I started writing in the Sixties. If I seem to be championing a moralistic way of looking at things it’s because there seems to be a very shallow aestheticism that’s taken over. It’s certainly not the aestheticism that I was associating myself with.

Oscar Wilde remains one of my idols. I haven’t changed. I don’t repudiate what I said then, but I hear echoes of a kind of superficial nihilism that seems associated with an aesthetic position that drives me up the wall. It seems that people have become so passive. When you mentioned the word energy, of course if I can see punk rock in that way I can feel it, and of course it’s not possible to get it by playing a couple of records on this inadequate stereo; you have to be in an audience. I remember the Academy of Music in 1964. What it was like to be in that audience that day was incredible.

High Times: You should go down to CBGB’s, that club on the Bowery.

Sontag: Yeah, I wanted to go down and see the Ramones.

High Times: You’ve said that what you’re personally looking for is art that would make you behave differently.

Sontag: Yeah, I’m looking for things that will change my life, right? And that of course will give me energy. And I don’t mean moral lessons in this dry sense, but something that would give me energy, that would also not simply provide me with this kind of fantasy alternative but would be an alternative that could be lived out, that would make my way of seeing things perhaps more complicated rather than less complicated.

See, I think a lot of what we get most pleasure out of is essentially simplifying. First of all, most of art in the last hundred years has been saying everything is terrible, and then it says the only thing one can do is resist the temptation of suicide, if that, or forget it, lie back, go with it, enjoy it, it doesn’t matter. It seems to me that one should be able to go beyond those alternatives. I don’t know how exactly.

High Times: How do you feel about the future of the planet?

Sontag: Terrified.

High Times: But people say that: “Terrified.” But I mean do you live in a state of fear?

Sontag: No, I don’t live in a state of fear, but I live in a state of desperate concern. I lead a life which is incredibly privileged. We were talking earlier about why I don’t make much money, but still just by virtue of being an American, by virtue of doing work that I want to do, that I would do whether I’m paid for it or not, by virtue of being white. I am in a tiny minority of people on this planet. So I don’t live in a state of terror; it would be presumptuous of me to be terrified, since I’m always so infinitely privileged just by being: one, American: two, white; and three, someone who’s not a wage slave. But how can one not be full of dread?

Just consider the demographic figure that India is adding 14,000,000 every year. That is to say, a hundred million people every six years. That’s when you subtract the deaths from the birth rates. More and more people go to bed hungry every night. More and more people are born than should be born. The environment is becoming more and more polluted, more and more carcinogenic. All kinds of systems of order are breaking down. Lousy as they may be, it’s not very likely that one’s going to replace them with a better one.

One of the few ideas that I formulated in a very simple way is that however bad things are, they can always get worse. Well, I got very tired in the Sixties with people who were saying that things couldn’t be any worse. The repression of the State, fascist America….Things were terrible, the Vietnam War was an abomination; but all kinds of terrible things have happened in this country, and things can always get worse. It’s wrong to say that things can’t get any worse. They can.

I think there are long-range ecological and demographic factors that don’t seem to be reversible, so that one thinks there will just be a series of catastrophes of one kind or another—world-wide famines or breakdowns of social systems, increasing amounts of political repression. That, I think, is the fate of most people in the world. I think the United States is in a very special position. I don’t think the breakdown of this system is imminent at all. But at what a cost to the rest of the world! I mean, the United States has 6 percent of the population of the world, and we’re using 60 percent of the resources and creating 60 percent of the garbage.

High Times: Does it annoy you?

Sontag: No, it doesn’t annoy me, it outrages me.

High Times: Yeah. I just find it hard to deal with those kinds of words, like terror and outrage. Because you’re outraged by this and yet, excuse me, but your latest book is—I find it a very interesting book— but it’s about photography.

Sontag: It’s not about photography!

High Times: Ah! Fair enough…

Sontag: (Laughing) Now you’ve got me. I said it, and I didn’t mean to say it. It’s not about photography, it’s about the consumer society, it’s about advanced industrial society. I finally make that clear in the last essay. It’s about photography as the exemplary activity of this society. I didn’t want to say it’s not about photography, but it’s true, and I guess this is the interview where that will finally come out. It isn’t, it’s about photography as this model activity which has everything that’s brilliant and ingenious and poetic and pleasureful in the society, and also everything that is destructive and polluting and manipulative in the society. It’s not, as some people have already said, against photography, it’s not an attack on photography.

High Times: I think you’re a great celebrator of photography.

Sontag: Well, of course it’s been one of the great sources of pleasure in my life, and it seemed to me obvious that that was the origin of the book. It’s about what the implications of photography are. I don’t want to be a photography critic. I’m not a photography critic. I don’t know how to be one.

I have gotten immense pleasure out of photographs. I collect them, cut them out, I’m obsessed by them; to me they’re sort of dream images, magical objects. I go to photography shows, I have hundreds of photography books. This is an interest that antedates not only the books, but it’s part of my whole life. But I think one can’t think about photography. This is a book that’s an attempt to think about what the presence of photography means, about the history of photography, about the implications of photography.

High Times: Do you think we’re going to see any extreme changes in this country within the next ten or fifteen years?

Sontag: I ask myself that all the time. A couple of years ago I would have said yes right away. Around ’73-’74 it seemed that things were changing very rapidly and for the worse. It seemed to me that there was obviously an immense reactionary current in the country, that things were going to be very depressing. One thing I want to disassociate myself from, although I’ve said some things that could contribute to it, is this facile repudiation of the Sixties. I mean the Sixties were a terrific time. It was the most important time in my life. If perhaps in the end we were too busy having a good time and thought things were a little simpler than they turned out to be, it doesn’t mean that most of what we learned isn’t very valuable; and we want to hang onto that and not be seduced by some kind of new simplification or this kind of pervasive demoralization of the Seventies.

I feel very irritated by the way people are so demoralized. What has gotten lost in the past few years is the critical sense. I mean what people finally took from the Sixties was that it was okay to do your own thing, that a lot of what seemed to be political impulse was in fact just some kind of pyschotherapeutic effort, and that what one thought or hoped was the growth of some kind of serious critical political atmosphere in the country proved to be an illusion. And so you have the same people who went to Vietnam demonstrations becoming the slaves of gurus and psychiatric quacks a couple of years later. That was disappointing. But it was on the whole a very positive change, I think.

High Times: Then your answer to the question is that at least at the moment you don’t see anything that suggests that we’ll see extreme changes here in the near future?

Sontag: I think the first thing to say is that this society is immensely powerful and that this regime, this system is immensely powerful, immensely successful, immensely entrenched, is very clever, has tremendous capacity for absorbing criticism and using it, not just silencing it but using it. And that there have to be real structural changes to make a difference, otherwise I think people are going to go on in this consumer way, riding along with things as far as they can, being drugged by consumer goods and averting their eyes to the pending catastrophe.

This country is so rich and so powerful and so privileged. I don’t think the present mood is anything other than transition. What I worry about much more is the growing force of reaction. That’s why I hate to be labeled as a moralist, because I think that an awful lot of bad things are going to happen in the name of moralism, and one has to be very suspicious.

High Times: How do you feel at this point about your future?

Sontag: I want to be a better writer. It seems it would be about getting better. To go on.

High Times: But you must feel that there are totally undiscovered things in front of you?

Sontag: If I didn’t feel that I could discover things that would be very different from what I’m doing, or if I didn’t feel that the work I’m doing is part of an approach to something… but I do feel that it’s always going somewhere. And yet there must be something wrong with that attitude, too. One could go on and on. Say I beat this rare illness and have a long, long life, would I then just go on forever saying I’m getting there, I’m getting there, I’m getting there, until one day my long life would be over?

Getting off the Road

Photo by John Anderson

Say you're broke.

Say you had an emergency root canal and your bank account balance has sunk dangerously low. You have a couple of choices. Either you make more money: Take on a second shift? Pawn your watch? Or you make your existing income go further, by cutting spending. Drop cable, cancel the gym membership, skip the lattes, and make drip coffee at home.

The quickest approach, and the solution that's already in your hands, is trimming your budget. Maybe you'll get a better job in the future, but you can be more frugal starting today.

It turns out the principles of personal budgeting also apply to traffic congestion. Viewed as a budget, Austin's roads are stretched to their limit. Building more roads – where there's room – is one solution, as is squeezing more efficiency out of the current system. But a more immediate one is easing the pressure on existing roads. And that's called "travel demand management," or TDM.

"It puts the solution more in the hands of residents," says Lauren Albright, Austin community manager for the carpooling app Carma. "When we talk to residents about Carma they're very receptive to the message, because they're so frustrated with transportation and traffic in Austin. They like the idea of taking the problem into their own hands, by taking extra cars off the road."

TDM happens through executive-level decisions, such as major employers allowing telecommuting, and individual choices, like an employee's decision to take the bus on Tuesdays instead of driving. Austin doesn't have a central command center for TDM – the city, CAMPO, TxDOT, and the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce all encourage it – although a local nonprofit called Movability Austin has the express purpose of helping Downtown employers implement TDM. It's not mandated by any level of government, though if Austin slips into nonattainment of federal air quality standards, that could change. Right now TDM strategies are voluntary, and focus on cost savings, quality of life, and mitigating the effects of congestion on Austin's booming economy.

TDM is a way out of the congestion nightmare predicted last year by the Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI), a research division of Texas A&M University, which tested possible long-term congestion fixes for I-35. Its Mobility Investment Priorities project modeled eight scenarios, including a baseline that added no capacity to I-35 but built all the roads and transit projects included in the existing 2035 Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization plan. If only the baseline projects are built, I-35 will be completely swamped by 2035, and travel across Austin during rush hour will take more than three hours, with heavy traffic continuing as late as 10pm some places.

Even the best-performing scenario – adding a pair of express lanes to the existing freeway, which is the option closest to TxDOT's current plans – netted a 5% reduction in vehicle-hours traveled (a measure of congestion). Wondering what would make a significant difference in congestion, the TTI team started modeling other options, experimentally – no matter how unrealistic. Its results were, on the one hand, a massive construction project: adding six tolled express lanes between SH 45 North and SH 45 South. On the other: a hybrid strategy that added the lane pair and aggressively reduced demand for the road. By increasing telecommuting, car- and vanpooling, online education, online shopping, transit, bike and pedestrian trips, and moving trips outside of rush hour, the team produced a model of I-35 in which traffic once again flowed freely. All of these are accepted strategies for reducing traffic, but again, they're not linked to any specific policies in Austin – TTI just modeled them to see what would ease congestion.

Meet the Enemy

The takeaway from the TTI report, its authors wrote, is that Central Texas can't ease congestion through road construction alone. This is partly because of the principle of "latent demand" – essentially the idea that if you build it, they will come. Chandra Bhat, director of UT's Center for Transportation Research (CTR), explains it this way: When a new lane or road opens, people use it for trips they hadn't made before the road opened, because it seems so convenient. Eventually, the new lanes fill up and the road returns to the level of congestion it had before the expansion. The time it takes to return to preconstruction congestion levels has been shrinking, Bhat says. And in Austin, "Essentially, the growth is happening so fast that it's impossible to build our way out of traffic congestion."

With a net gain of 110 new residents a day, who bring with them about 70 cars, Austin is growing too fast for its roads to accommodate the traffic. And according to the 2012 American Community Survey, 76% of workers in Central Texas drove alone to work each day.

The other key lesson from the TTI report, says City of Austin Transportation Director Rob Spillar, is that 86% of I-35 traffic in Austin is local – trips originating or ending in the Austin metro area. TTI concluded that, contrary to armchair wisdom, any congestion solution predicated on rerouting through traffic around town – such as to SH 130 – will fall short. "We've seen the enemy, and the enemy is us," Spillar says.

Bhat and Spillar emphasize that Austin has to take an "all of the above" approach to its traffic problems, building roads and transit and promoting TDM. But the latter can be accomplished much more cheaply and quickly, and without a single vote or traffic cone. "Any of these big infrastructure projects, whether it be rail, or improvements to I-35, or improvements to Lamar – they'll take six to 10 years to get on the ground," Spillar says. "In the meantime, we need to get 40,000 more people Downtown for the new employment that's being constructed right now."

Time and Place

So how can that happen?

"The decisions to participate in any of the demand management programs have to be made by and large in the private sector and by individuals, so it's not something that can be forced upon people, and probably shouldn't be," says Randy Machemehl, a professor of transportation engineering at CTR. "But it has been slow to be incorporated as a result of that."

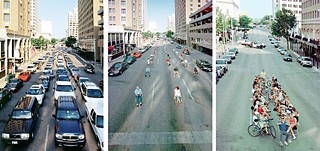

The Austin version of the space required to accommodate the same number of people in cars, on foot, or on bicycles. (Photos courtesy of Movability Austin)

A couple of local initiatives are trying to speed up the process. Movability Austin, formed in 2011, is a transportation management association (TMA) with 35 member organizations. TMAs, a type of nonprofit that's found across the country, help employers and commuters reduce car trips in a particular geographic area. And the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce, which last year engaged TTI to model traffic-reduction strategies, is encouraging its members to adopt at least one demand-reduction practice. "One of the biggest challenges our local businesses face is traffic," says Regional Infrastructure Senior Vice President Jeremy Martin. "We're not asking you to implement it all, but if traffic is a concern, we ask that you own the solution and evaluate the opportunities you have to implement mobile workforce, flexible scheduling, buying transit passes for employees, or evaluating your location to reduce the length of trips."

One solution is for companies to stop asking all their employees to physically arrive at work by 9am and leave around 5pm. There are other times of day, Spillar points out, when major arteries are relatively clear. If travel could be distributed more evenly throughout the day, the roads could better handle the demand. Or travel could be eliminated entirely with telecommuting.

The more idea-based an economy, the more suitable it is for telecommuting. While Central Texas, with 7% of workers telecommuting, is a national leader in the practice (also called "teleworking" or "mobile workforce"), that option isn't widely used by Downtown employers. Companies located Downtown pay a premium for office space there for a specific reason, says Glenn Gadbois, executive director of Movability Austin. They want to be close to Downtown colleagues, restaurants, and social spaces, and "that can't be easily substituted with a strong and seriously productive telework policy," he says. This is even more true of northeast Downtown's anticipated "Innovation Zone," beside the medical school complex, whose calling card will be the multiplication of ideas fostered by density.

But Dell and AMD, located outside Downtown, do use telecommuting. In the past, says Justin Murrill, AMD's global sustainability manager, the company saw roughly 10-20% of its employees teleworking at least once a week. For over a year AMD has run a pilot program to see if employees could work from home more frequently, or if perhaps some didn't need a workspace on the Southwest Parkway campus at all. The company developed criteria for assessing who could telework and a training for both employees and managers, and its follow-up surveys have shown positive feedback from both groups.

Embracing teleworking does require a shift to a performance-based management model, Murrill says. "It's my opinion that, in general, if you're used to seeing somebody sitting at their desk 9 to 5, and instead you're basing their performance on the quality and timeliness of their deliverables, that's a very different management style. It's clear there are certain instances of where teleworking is valued and wanted, and it delivers environmental and parking benefits – and then there are some concerns any company has about teleworking being misapplied."

Other options for employers include flexible hours (one employee on a project works from 7-4, and another works from 9-6), or related strategies like requiring core office hours (employees have flexibility to work from home as long as they're in the office from 10-3, when team meetings are scheduled), or allowing compressed workweeks (an employee works four 10-hour shifts), as some TxDOT departments do.

Filling Empty Seats

If employees still have to come to the office, they could use fewer vehicles to get there. Carpooling is experiencing somewhat of a renaissance, in part due to new apps that help workers find a ride. And the math is easy: "If every person driving alone in Austin offered an empty seat to another person, we could cut the number of cars on the road in half," says Lauren Albright of Carma, which launched in Austin in February.

Carma frames the congestion problem as a waste of empty seats rather than crowded roads. And it has a point: Carma cites census data suggesting nearly 938,000 empty seats languish in solo commuters' cars. To overcome the obstacle of finding someone to ride with, the app offers a system to match potential carpool members, whose numbers reached 1,000 this month. Users enter their typical commute schedule and route and are matched with other people who are located nearby and have similar schedules. While it can be used on the fly – say you took the bus Downtown and need to get back home – the service is focused more on regular commutes than one-time rides. Unlike services like Lyft and Uber, its drivers are not allowed to make a profit.

The company came to Austin on a federal grant to test its technology for verifying carpools and offering them free rides on toll roads. If Carma members carpool on 183A or the Manor Expressway – toll roads that are part of the pilot program – their toll costs are reimbursed. The company, which is partnering with the Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority, tracks carpoolers' travel via the app and the GPS on their phones. After comparing its data with the toll vendor's, Carma reimburses the driver's toll costs.

Commute Solutions, a CAMPO initiative, also offers a ride-matching service as part of its two-year-old myCommuteSolutions site, which counts 2,800 members. Program Coordinator Julie Mazur has also established custom subsites for businesses like Samsung that allow their employees to find carpools within the company.

The RideScout app offers similar features, though it's meant to be used as much on the fly as it is for regular commutes. The app shows travelers a host of options for reaching their destination – driving alone, bikeshare, bus, carshare, taxi, walking, or carpooling with whoever's nearby.

To reduce stranger danger, Carma and RideScout offer the option to search only within certain groups, such as residents of the same neighborhood or employees of the same large company. MyCommuteSolutions lets users filter potential commute partners by gender and whether they smoke, and it doesn't show users' exact home or work addresses.

Central Texans who want to share rides without sharing their personal vehicle can participate in Capital Metro's RideShare vanpooling program, which provides vans and underwrites some of their lease cost. Typically one person does the driving, and new members can find a vanpool (there are 122 of them) via Capital Metro's website.

Breaking the Chains

One other solution has less to do with how people travel, and more about where they're going. Those patterns are different than they were 50 years ago.

Bhat says Austin's challenge is not just its population growth, but the composition of that growth. Demographic trends show an increase in the number of single-adult households and single-parent families; the "traditional" family with two adults, one of whom works outside the home, is less common. The practical effect on traffic is a longer rush hour, as workers squeeze more errands into their commutes, a practice engineers call "chaining." In past decades the nonworking spouse could often go to the bank, grocery store, and cleaners in the middle of the day while her partner was at work. Today, more single parents run these errands and pick up kids from daycare or school after work. More adults in dual-earner households are running errands, and sometimes picking up the kids, as part of their commute. And young, single adults tend to go out – to the gym, to happy hour – rather than going straight home. All of these demographic shifts affect traffic patterns, Bhat says.

One of the most macro-level steps suggested for combating congestion is shifting land use patterns to create more "centers" that combine jobs, housing, and services that would otherwise be "chained" into the commute. Placing essential services like groceries and child care near transit stops also takes pressure off the commute, since people could pick up the kids, the dry cleaning, or dinner on their walk home from the transit stop, or on their drive home from the Park & Ride.

The Chamber's Jeremy Martin says the CodeNEXT Land Development Code revision is an opportunity to make that happen. "When it comes to locating more jobs near existing housing, and vice versa, our land development code does not allow for flexibility and the diversity of uses necessary to shorten those work trips," he says, and points for an example of success to the 2004 University Neighborhood Overlay that encouraged more density in West Campus. Demand for housing near UT was very high, "and allowing for the market to build to that demand has allowed students to move back near campus" from areas like Riverside Drive, reducing commuter trip length, Martin says.

"The takeaway message is that transportation cannot stand on its own," says Bhat. "Let's build our communities and design our land use in such a way that it reinforces transportation services."

Parking policies, too, can have an effect on commuter behavior. Plentiful, inexpensive parking encourages driving, while limited parking encourages other modes of transit. "The general philosophy on parking and travel demand is that people are more likely to drive when there's a free parking space waiting for them at the end of their journey," explains Leah Bojo, a policy aide to Council Member Chris Riley, who sponsored a successful 2012 resolution to remove minimum parking requirements Downtown.

A lack of parking is one of the biggest reasons Downtown employers contact Movability Austin about alternative transportation options. In such situations, companies might encourage, and even subsidize, their employees to buy a bus or rail pass or a carshare membership instead of a parking space. Even businesses that have historically offered parking as an employee benefit are switching to parking cash-out programs as Downtown parking spots become more scarce.

The UT campus is an extreme example of parking scarcity: The campus has about 15,000 parking spaces and a daytime population of 70,000 students, faculty, and staff. Parking permits start at $142 for faculty and staff, but a Capital Metro bus pass is an automatic employee benefit. The campus also contracts with Zipcar, runs a 1,500-member carpool program, counts 10,000 active bicycle registrants, and works to improve the pedestrian experience from West Campus to encourage students to walk.

Find What Drives You

Implementing any of these strategies requires a careful look at people's barriers to altering their commutes as well as the motivations to surmount those barriers. AMD's Justin Murrill says that one of the first steps in the company's redesign of its Go Green – Commute program was a survey of all Austin employees about their obstacles and motivations for using different modes of transit. They then found incentives to help push past people's resistance – a ride-matching tool to help form carpools; bike racks, showers, and a reward system of store credit at Mellow Johnny's Bike Shop for bike commuters.

Identifying these barriers and finding ways around them is Movability Austin's bread and butter. When Movability surveys companies, it typically finds that 15-20% of employees have already figured out an alternative commute. Another 20-25% are interested in alternatives but aren't really using them – "and that's our sweet spot," says Executive Director Gadbois, adding that his group doesn't spend any time trying to force a change on those who aren't interested. Movability then acts as a one-stop shop to help receptive employees find their options. This means everything from sitting down with one person and mapping a safe bike route with minimal hills, to talking with an employer about offering transit passes instead of garage parking.

People are reluctant to give up their car keys for a host of reasons. They have kids who need to be dropped at school and picked up from practice. They have errands to run. They enjoy the time alone in the car. They just don't like change.

Some of these are easier to surmount than others. Capital Metro's Guaranteed Ride Home program can assuage the fears of transit or carpool users who worry about an emergency occurring on a day they don't have the car. And for Downtown workers, at least, B-cycle, Zipcar, and Car2Go offer ways to run errands in the middle of the day, eliminating them from the rush hour "chain."

One of the biggest barriers is sheer anxiety about trying something new. (How do I pay the fare on the bus? Where do I sit? How do I tell the driver I want to get off at this stop?) Start small, Gadbois and Mazur say: Plan your trip on Capital Metro's website or with a bike map, and try it on a weekend when you have plenty of time. If you're still hesitant, you can indicate on your profile with myCommuteSolutions that you'd like to be paired with an experienced bike or transit commuter who can show you how.

But why try taking the bus to work in the first place? Gadbois says the best motivators for any sort of change are internal. Your average commuter may not be particularly motivated to improve air quality, but he might like the cost savings associated with carpooling, or the exercise from the bike ride, or the time gained to read on the train. Part of Gadbois' job is to help people identify their own motivators by pushing them to try an alternative commute the first few times, and often that process involves competition.

Movability members like HomeAway "gamify" the testing of new commute options by setting up contests. Last May, HomeAway challenged its employees to bike to work as much as possible and rewarded the participants with breakfast tacos and happy hour (the winners got prizes, too). Commute Solutions runs contests through its commute-logging tool; AMD celebrates whatever global campus has the most participation in bike-to-work day (Fort Collins, 40%). The point in each exercise is to introduce people to their options and help them find a motivation for continuing to use them.

Once an employee finds a new option that works, the company needs to support that, says Thomas Butler, the Downtown Austin Alliance's streetscapes and transportation director. "It's not just giving them transportation options, it's giving them support services to enable them to use those options. It's not just saying, 'You can bike to work,' it's putting in place the bike infrastructure that makes cycling safe; it's putting in showers at the end of their trips; it's putting in bike lockers so people can lock up their bikes and feel they're safe." And it's not an all-or-nothing proposition, says Gadbois: "We really want people to do it one day a week, do it two days a week. It's not black or white. You don't just have to be a bicyclist, you don't just have to be a bus rider."

To return to the budget metaphor: If you're trying to save money, you don't have to brown-bag it every day for the rest of your life. But if you do so consistently twice a week, the savings will add up. The same principle applies to congestion.

"I tell my class we could solve the congestion problem overnight, and we wouldn't have to build anything or buy anything," says CTR's Machemehl. "They say, 'Wow, this guy is a genius.' No, I'm just talking about carpooling. If you put two people in every car instead of one, that's easy math."

And it's immediate. For Julie Mazur of CAMPO, "There's lots of good projects going on – Project Connect, Mobility 35 – but that's the future. This is something you can do today."

Interview with BJP leader Narendra Modi

By Ross Colvin and Sruthi Gottipati

Narendra Modi is a polarising figure, evoking visceral reactions across the political spectrum. Critics call him a dictator while supporters believe he could make India an Asian superpower. (Read a special report on Modi here)

Reuters spoke to Modi at his official Gandhinagar residence in a rare interview, the first since he was appointed head of the BJP’s election campaign in June.

Here are edited excerpts from the interview. The questions are paraphrased and some of Modi’s replies have been translated from Hindi.

Do you regret what happened?I’ll tell you. India’s Supreme Court is considered a good court today in the world. The Supreme Court created a special investigative team (SIT) and top-most, very bright officers who overlook oversee the SIT. That report came. In that report, I was given a thoroughly clean chit, a thoroughly clean chit. Another thing, any person if we are driving a car, we are a driver, and someone else is driving a car and we’re sitting behind, even then if a puppy comes under the wheel, will it be painful or not? Of course it is. If I’m a chief minister or not, I’m a human being. If something bad happens anywhere, it is natural to be sad.

Should your government have responded differently?Up till now, we feel that we used our full strength to set out to do the right thing.

But do you think you did the right thing in 2002?Absolutely. However much brainpower the Supreme Being has given us, however much experience I’ve got, and whatever I had available in that situation and this is what the SIT had investigated.

Do you believe India should have a secular leader?We do believe that … But what is the definition of secularism? For me, my secularism is, India first. I say, the philosophy of my party is ‘Justice to all. Appeasement to none.’ This is our secularism.

Critics say you are an authoritarian, supporters say you are a decisive leader. Who is the real Modi?If you call yourself a leader, then you have to be decisive. If you’re decisive then you have the chance to be a leader. These are two sides to the same coin … People want him to make decisions. Only then they accept the person as a leader. That is a quality, it’s not a negative. The other thing is, if someone was an authoritarian then how would he be able to run a government for so many years? … Without a team effort how can you get success? And that’s why I say Gujarat’s success is not Modi’s success. This is the success of Team Gujarat.

What about the suggestion that you don’t take criticism?I always say the strength of democracy lies in criticism. If there is no criticism that means there is no democracy. And if you want to grow, you must invite criticism. And I want to grow, I want to invite criticism. But I’m against allegations. There is a vast difference between criticism and allegations. For criticism, you have to research, you’ll have to compare things, you’ll have to come with data, factual information, then you can criticize. Now no one is ready to do the hard work. So the simple way is to make allegations. In a democracy, allegations will never improve situations. So, I’m against allegations but I always welcome criticism.

On his popularity in opinion pollsI can say that since 2003, in however many polls have been done, people have selected me as the best chief minister. And as best chief minister, it wasn’t just people from Gujarat who liked me, not like that. People outside of Gujarat have also voted like that for me. One time, I wrote a letter to the India Today Group’s Aroon Purie. I requested him – “Every time I’m a winner, so next time please drop Gujarat, so someone else gets a chance. Or else I’m just winning. Please keep me out of the competition. And besides me, give someone else a shot at it.”

Allies and people within the BJP say you are too polarizing a figureIf in America, if there’s no polarization between Democrats and Republicans, then how would democracy work? It’s bound (to happen). In a democracy there will be a polarization between Democrats and Republicans.

This is democracy’s basic nature. It’s the basic quality of democracy. If everyone moved in one direction, would you call that a democracy? But allies and partners still find you controversialUp till now, no one from my party or the people who are allied with us, I’ve never read nor heard any official statement (about this from them). It might have been written about in the media. They write in a democracy … and if you have any name that this person is there in the BJP who said this, then I can respond.

But allies and partners still find you controversialUp till now, no one from my party or the people who are allied with us, I’ve never read nor heard any official statement (about this from them). It might have been written about in the media. They write in a democracy … and if you have any name that this person is there in the BJP who said this, then I can respond.

How will you persuade minorities including Muslims to vote for you?First thing, to Hindustan’s citizens, to voters, Hindus and Muslims, I’m not in favour of dividing. I’m not in favour of dividing Hindus and Sikhs. I’m not in favour of dividing Hindus and Christians. All the citizens, all the voters, are my countrymen. So my basic philosophy is, I don’t address this issue like this. And that is a danger to democracy also. Religion should not be an instrument in your democratic process.

If you become PM, which leader would you emulate?The first thing is, my life’s philosophy is and what I follow is: I never dream of becoming anything. I dream of doing something. So to be inspired by my role models, I don’t need to become anything. If I want to learn something from Vajpayee, then I can just implement that in Gujarat. For that, I don’t have to have dreams of (higher office in) Delhi. If I like something about Sardar Patel, then I can implement that in my state. If I like something about Gandhiji, then I can implement that. Without talking about the Prime Minister’s seat, we can still discuss, that yes, from each one we have to learn the good things.

On the goals the next government should achieve Look, whichever new government comes to power, that government’s first goal will be to fix the confidence that is broken in people.The government tries to push a policy. Will it continue that policy or not? In two months, if they face pressure, will they change it? Will they do something like — an event happens now and they’ll change a decision from 2000? If you change decisions from the past, you will bring the policy back-effects. Who in the world will come here?So whichever government comes to power, it would need to give people confidence, it should build the trust in people, “yes, in policies there will be consistency”, if they promise people something, they will honor that promise, they will fulfil. Then you can position yourself globally.

Look, whichever new government comes to power, that government’s first goal will be to fix the confidence that is broken in people.The government tries to push a policy. Will it continue that policy or not? In two months, if they face pressure, will they change it? Will they do something like — an event happens now and they’ll change a decision from 2000? If you change decisions from the past, you will bring the policy back-effects. Who in the world will come here?So whichever government comes to power, it would need to give people confidence, it should build the trust in people, “yes, in policies there will be consistency”, if they promise people something, they will honor that promise, they will fulfil. Then you can position yourself globally.

People say economic development in Gujarat is hyped upIn a democracy, who is the final judge? The final judge is the voter. If this was just hype, if this was all noise, then the public would see it every day. “Modi said he would deliver water.” But then he would say “Modi is lying. The water hasn’t reached.” Then why would he like Modi? In India’s vibrant democracy system, and in the presence of vibrant political parties, if someone chooses him for the third time, and he gets close to a two-third majority then people feel what is being said is true. Yes, the road is being paved, yes, work is being done, children are being educated. There are new things coming for health. 108 (emergency number) service is available. They see it all. So that’s why someone might say hype or talk, but the public won’t believe them. The public will reject it. And the public has a lot of strength, a lot.

Should you be doing more for inclusive economic growth?Gujarat is a state that people have a lot of expectations from. We’re doing a good job, that’s why the expectations are high. As they should be. Nothing is wrong.

We do believe in inclusive growth, we do believe that the benefits of this development must reach to the last person and they must be the beneficiary. So this is what we’re doing.

People want to know who is the real Modi – Hindu nationalist leader or pro-business chief minister?I’m nationalist. I’m patriotic. Nothing is wrong. I’m a born Hindu. Nothing is wrong. So, I’m a Hindu nationalist so yes, you can say I’m a Hindu nationalist because I’m a born Hindu. I’m patriotic so nothing is wrong in it. As far as progressive, development-oriented, workaholic, whatever they say, this is what they are saying. So there’s no contradiction between the two. It’s one and the same image.

On Brand Modi and people behind the PR strategyThe western world and India – there’s a huge difference between them. Here, India is such a country that a PR agency will not be able to make a person into anything. Media can’t make anything of a person. If someone tries to project a false face in India, then my country reacts badly to it. Here, people’s thinking is different. People won’t tolerate hypocrisy for very long. If you project yourself the way you actually are, then people will accept even your shortcomings. Man’s weaknesses are accepted. And they’ll say, yes, okay, he’s genuine, he works hard. So our country’s thinking is different. As far as a PR agency is concerned, I have never looked at or listened to or met a PR agency. Modi does not have a PR agency. Never have I kept one.

(You can follow Ross on Twitter at @rosscolvin and Sruthi @GoSruthi)

For timeline on the rise of Modi, click here

For a picture profile of Modi, click here

For Modi’s statements that made news; click here

Comments

Post a Comment