The Libertarian Movement Needs a Kick in the Pants

In a provocative yet thoughtful manifesto, economist Tyler Cowen, a major figure in libertarian circles, offers a harsh assessment of his ideological confreres:

Having tracked the libertarian "movement" for much of my life, I believe it is now pretty much hollowed out, at least in terms of flow. One branch split off into Ron Paul-ism and less savory alt right directions, and another, more establishment branch remains out there in force but not really commanding new adherents. For one thing, it doesn't seem that old-style libertarianism can solve or even very well address a number of major problems, most significantly climate change. For another, smart people are on the internet, and the internet seems to encourage synthetic and eclectic views, at least among the smart and curious. Unlike the mass culture of the 1970s, it does not tend to breed "capital L Libertarianism." On top of all that, the out-migration from narrowly libertarian views has been severe, most of all from educated women.

As an antidote, Cowen champions what he calls "State Capacity Libertarianism," which holds that a large, growing government does not necessarily come at the expense of fundamental individual rights, pluralism, and the sort of economic growth that leads to continuously improved living standards. Most contemporary libertarians, he avers, believe that big government and freedom are fundamentally incompatible, to which he basically answers, Look upon Denmark and despair: "Denmark should in fact have a smaller government, but it is still one of the freer and more secure places in the world, at least for Danish citizens albeit not for everybody."

In many ways, Cowen's post condenses his recent book Stubborn Attachments, in which he argues politics should be organized around respect for individual rights and limited government; policies that encourage long-term, sustainable economic growth; and an acknowledgement that some problems (particularly climate change) need to be addressed at the state rather than individual level. You can listen to a podcast I did with him here or read a condensed interview with him here. It's an excellent book that will challenge readers of all ideological persuasions. There's a ton to disagree with in it, but it's a bold, contrarian challenge to conventional libertarian attitudes, especially the idea that growth in government necessarily diminishes living standards.

I don't intend this post as a point-by-point critique of Cowen's manifesto, whose spirit is on-target but whose specifics are fundamentally mistaken. I think he's right that the internet and the broader diffusion of knowledge encourages ideological eclecticism and the creation of something like mass personalization when it comes to ideology. But this doesn't just work against "capital L Libertarianism." It affects all ideological movements, and it helps explain why the divisions within groups all over the political spectrum (including the Democratic and Republican parties) are becoming ever sharper and harsher. Everywhere around us, coalitions are becoming more tenuous and smaller. (This is not a bad thing, by the way, any more than the creation of new Christian sects in 17th-century England was a bad thing.) Nancy Pelosi's sharpest critics aren't from across the aisle but on her own side of it. Such a flowering of niches is itself libertarian.

Cowen is also misguided in his call for increasing the size, scope, and spending of government. "Our governments cannot address climate change, much improve K-12 education, fix traffic congestion," he writes, attributing such outcomes to "failures of state capacity"—both in terms of what the state can dictate and in terms of what it can spend. This is rather imprecise. Whatever your beliefs and preferences might be on a given issue, the scale (and cost) of addressing, say, climate change is massive compared to delivering basic education, and with the latter at least, there's no reason to believe that more state control or dollars will create positive outcomes. More fundamentally, Cowen conflates libertarianism with political and partisan identities, affiliations, and outcomes. I think a better way is to define libertarian less as a noun or even a fixed, rigid political philosophy and more as an adjective or "an outlook that privileges things such as autonomy, open-mindedness, pluralism, tolerance, innovation, and voluntary cooperation over forced participation in as many parts of life as possible." I'd argue that the libertarian movement is far more effective and appealing when it is cast in pre-political and certainly pre-partisan terms.

Be all that as it may, I agree that the libertarian movement is stalled in some profound ways. A strong sense of forward momentum—what Cowen calls flow—among self-described libertarians has definitely gone missing in the past few years, especially when it comes to national politics (despite the strongest showing ever by a Libertarian presidential nominee in 2016). From the 1990s up through a good chunk of the '00s, there was a general sense that libertarian attitudes, ideas, and policies were, if not ascendant, at least gaining mindshare, a reality that both energized libertarians and worried folks on the right and left. In late 2008, during the depths of the financial crisis and a massive growth of the federal government, Matt Welch and I announced the beginning of the "Libertarian Moment." This, we said, was

an early rough draft version of the libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick's glimmering "utopia of utopias." Due to exponential advances in technology, broad-based increases in wealth, the ongoing networking of the world via trade and culture, and the decline of both state and private institutions of repression, never before has it been easier for more individuals to chart their own course and steer their lives by the stars as they see the sky.

Our polemic, later expanded into the book The Declaration of Independents, was as much aspirational as descriptive, but it captured a sense that even as Washington was about to embark on a phenomenal growth spurt—continued and expanded by the Obama administration in all sorts of ways, from the creation of new entitlements to increases in regulation to expansions of surveillance—many aspects of our lives were improving. As conservatives and liberals went dark and apocalyptic in the face of the economic crisis and stalled-out wars and called for ever greater control over how we live and do business, libertarians brought an optimism, openness, and confidence about the future that suggested a different way forward. By the middle of 2014, The New York Times was even asking on the cover of its weekly magazine, "Has the 'Libertarian Moment Finally Arrived?"

That question was loudly answered in the negative as the bizarre 2016 presidential season got underway and Donald Trump appeared on the horizon like Thanos, blocking out the sun and destroying all that lay before him. By early 2016, George Will was looking upon the race between Trump and Hillary Clinton and declaring that we were in fact not in a libertarian moment but an authoritarian one, regardless of which of those monsters ended up in the White House. In front of 2,000 people gathered for the Students for Liberty's annual international conference, Will told Matt and me:

[Donald Trump] believes that government we have today is not big enough and that particularly the concentration of power not just in Washington but Washington power in the executive branch has not gone far enough….Today, 67 percent of the federal budget is transfer payments….The sky is dark with money going back and forth between client groups served by an administrative state that exists to do very little else but regulate the private sector and distribute income. Where's the libertarian moment fit in here?

With the 2020 election season kicking into high gear, apocalypticism on all sides will only become more intense than it already is. Presidential campaigns especially engender the short-term, elections-are-everything partisan thinking that typically gets in the way of selling libertarian ideas, attitudes, and policies.

Cowen is, I think, mostly right that the libertarian movement is not "really commanding new adherents," including among "educated women." He might add ethnic and racial minorities, too, who have never been particularly strongly represented in the libertarian movement. And, increasingly, younger Americans, who are as likely to have a positive view of socialism as they are of capitalism.

Of course, as I write this, I can think of all sorts of ways that libertarian ideas, policies, and organizations actually speak directly to groups not traditionally thought of libertarian (I recently gave $100 to Feminists for Liberty, a group that bills itself as "anti-sexism & anti-statism, pro-markets & pro-choice.") School choice, drug legalization, criminal justice reform, marriage equality, ending occupational licensing, liberalizing immigration, questioning military intervention, defending free expression—so much of what defines libertarian thinking has a natural constituency among audiences that we have yet to engage as successfully as we should. That sort of outreach, along with constant consideration of how libertarian ideas fit into an ever-changing world, is of course what Reason does on a daily basis.

All of us within the broadly defined libertarian movement need to do better. And in that sense at least, Cowen's manifesto is a welcome spur to redoubling efforts.

Video: We Went to Taiwan & Made a Bike from the Future - The Grim Donut

A PINKBIKE ORIGINAL

THE GRIM DONUT

Part 1: we went to Taiwan & made a bike from the future...

Words by Mike Levy

What happens when a joke becomes reality?

It took tens of millions of years for the opposable thumb to show up, and only slightly less time for mountain bike geometry to get to the point where our bikes aren’t actively trying to kill us. This whole evolution thing is a long, slow process.

Just one ride on a machine from a decade ago is all it takes to realize that development hasn't been standing still—bikes these days are damn good. But it sure does seem unhurried sometimes.

Brands design bikes to sell them, shocking I know. From a business perspective there’s just not a lot of upside to taking huge risks in the geometry department. So for all their talk of "game-changing" and "revolutionary," it makes sense for many brands to design bikes to be on-trend next year rather than roll the dice on what might be the future. Something risky may not win over customers, even if it's the future.

Yes, there are outliers, the people making wild things in their workshops, and occasionally the established brands can be adventurous, too. But, for the most part, the industry seems to be pushing the envelope forward by about, oh I don’t know, a single degree and a handful of millimeters every few years. At this rate, bikes will have their own opposable thumbs in another twenty million years...

But what if we skipped the evolution part and went straight to revolution?

We've spent the last few years talking half-seriously about how we should just extrapolate where mountain bike development *might be* by pressing the fast-forward button. So what happens when a joke becomes reality and we do exactly that? We're going to find out.

Of course, bikes are really damn good these days, and steady evolution is probably in most riders' best interests... but in the name of “science” or something, it's time to take things a little too far by building a bike from the future. A very long and slack future, it turns out.

Geometry from 2030

The first step was to figure out what bikes would look like in ten years, and we didn't need one of those ''engineer'' types to figure that one out. Wheel size debates and chainstay lengths come and go, but if we see “longer and slacker” in one more press kit…

And unlike developing a new suspension design, geometry doesn't cost anything.

Go back a decade and lots of bikes had head angles hovering around 69-degrees, seat angles that felt about the same, and front-end lengths best suited to small children. Yeah, things were cramped and we flipped over the bars a lot.

So to get to our geometry from the future, we just took the numbers from 2010, punched them into our 2020 digital extrapolator, and boom, we had the numbers we'll be using in 2030. Hey everyone, you're welcome.

From custom carbon to catalog aluminum

The best-laid plans often go awry, but that doesn't apply here given that our plans weren't laid all that well.

The dream of letting the factories fight over who was going to manufacture our wacky design was destined to be drowned in bubble tea. Tongue-in-cheek impossible suspension design aside, the startup costs for custom carbon fiber construction would have been far, far too high. Sure, we could have pulled a Tesla and pre-sold some bikes to pay for building them, but we’re too irresponsible to have that hanging over our heads.

Instead, the idler pulley, dual-link suspension layout (High Pivot Virtual™) and carbon construction were abandoned in favor of an already-designed catalog frame—but built with our 2030 geometry. This is where Genio, a relatively small but high-end Taiwanese factory, enters the story with their 160mm-travel GF7-1-160A frame.

You can call it the Grim Donut.

What have we done?

With headtube angles pushing 63° these days, we had to go all the way to 57°. Along the same misguided lines, we've got some modern bikes with seattube angles around 78°, so we added 5° to get to an 83° seattube angle.

Hey, this geometry thing really isn’t all that hard after all.

Reach ended up be decided for us. We were constrained to 500mm because we didn't want to order a bunch of custom tubes or weld two toptubes together, but that seems like a big number so it's probably correct. And then we decided to call it a small-sized frame because, despite the long reach, the super-steep seat angle means the effective toptube length is actually a hair shorter than many small bikes on the market. But in a neat trick, it’s pretty damn big when you stand up! The seat tube is just 400mm tall, too.

If wheels have gotten larger over time, they're probably going to keep getting larger, right? No doubt, which is why we originally looked into making a 29"/32" wheel size combo (sorry). All we got were blank stares and dial tones when we tried to show tire companies the future, though, so our project had to roll on a 27.5"/29" mullet setup. The small rear wheel does allow for conservative 450mm chainstays (we wouldn’t want to get too crazy, right?). Other numbers include 155mm-long children’s cranks, and a 180mm fork mated to 160mm of rear-wheel-travel.

Genio took our geometry numbers, double and triple checked with us to make sure it was actually what we wanted for some reason, and then lit the torch. Eight long weeks later a box arrived at Pinkbike HQ with the very first Grim Donut prototype inside of it.

The build

We assume that by 2030 all suspension will be attached directly to our brains via Bluetooth, but for now we went with a RockShox Lyrik and Super Deluxe Coil Ultimate. SRAM won the Innovation of the Year and I'd put money on them being the first to try implementing that brain-implanted suspension microchip, so hopefully they'll offer an upgrade kit. We did try flipping the crown around to shorten the offset, but it ended up contacting the arch and we could feel the SRAM techs' disapproving eye-rolls from miles away.

It's obvious that drivetrains will keep having fewer and fewer gears when you look at the trends since the "glory days" of 27-speed bikes, so we went ahead and chose SRAM's 8-speed eMTB drivetrain. And shrinking crank lengths made it obvious that we had to run SRAM's 155mm kids' bike crankset. It actually looks super badass. TRP eMTB brakes with chonky rotors keep the e-bike theme going, along with e*thirteen's wheels and tires. We're also sticking with the OneUp dropper post because it'll probably still be running fine in ten years, and someone is weirdly obsessed with those weird looking Tioga saddles...

And the rest is, errrr, history.

Stay tuned for part 2 - can you skip evolution? Has the Grim Donut gone too far or is it the right amount of stupid? We'll find out in the next episode.

Created byBrian Park & Jason Lucas

Produced & Directed byJason Lucas

StarringMike Levy, Mike Kazimer,Calvin Lin, & Yoann Barelli

Additional Footage byMax Barron & Chris Ricci

Words byMike Levy & Brian Park

Photography byBrian Park

Special Thanks toGenio Bikes, Taipei Cycle Show, TAITRAAstro, A-Mega, A Pro, Waki Designs forthe Grim Donut drawings, Duncan Riffleat SRAM, Connor Bondlow at e*ThirteenSam Richards at OneUp, Cody Philips,TRP Brakes, Chris Cocalis at Pivot, TheAava Whistler Hotel, Nick Morgan atCorsa Cycles, Karl & Radek Burkat

Poll: Federal Budget Deficit Is a Bigger Problem Than Climate Change, Racism, and Terrorism

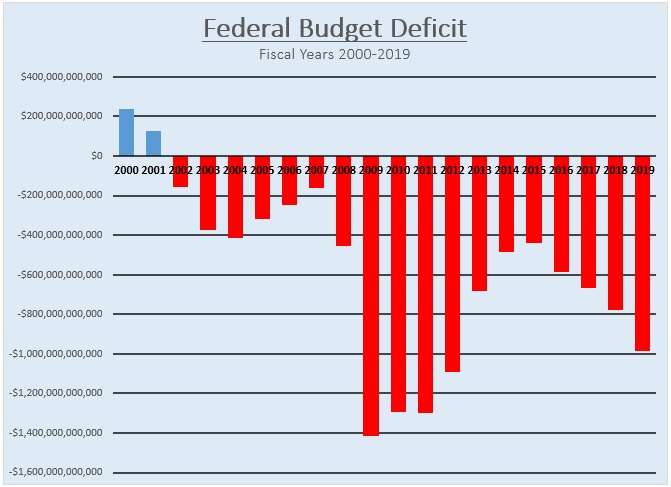

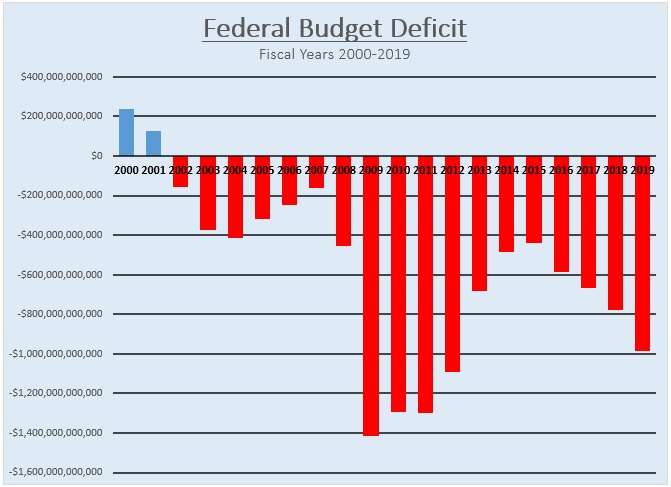

The year 2020 will almost certainly mark a return to trillion-dollar federal deficits despite a full decade of consistent economic growth.

Most Americans are well aware that's a worrying combination. Unfortunately, that message hasn't reached policymakers in Washington, D.C., who seem happy to add ever larger sums to the bill future taxpayers will have to pay.

A Pew Research Center poll conducted earlier this month found that 53 percent of Americans view the federal budget deficit as a "very big" problem facing the country. That's a larger share of the public than the portion that views terrorism (39 percent), racism (43 percent), or climate change (48 percent) as a major problem.

Indeed, the only topics that score higher in the Pew poll are drug addiction and the affordability of health care and college educations. But while you'll hear lots of discussion about those three issues in next year's presidential campaigns, candidates will likely give considerably less attention to the deficit, even as it soars past the trillion-dollar threshold. That's because reducing the deficit requires a serious and difficult discussion about how the federal government can and should allocate its finite resources. It's much easier to promise student loan forgiveness and/or massive new health care entitlement spending.

Other recent polls show similar levels of concern about the deficit and the $23 trillion national debt. A YouGov/The Economist survey published in July found that 83 percent of Americans said the budget deficit was an important issue. A Gallop poll in March found that 95 percent of Americans worry at least a little about the national debt, including 50 percent who say they worry "a great deal" about it.

This year's Fiscal Confidence Index—which is published by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation and tracks Americans' confidence in the country's fiscal stability—found that 76 percent of voters want Congress to work on reducing the deficit, including 72 percent of Democrats and 84 percent of Republicans.

The problem, as always, is that voters are likely to say they want Congress to balance the budget, but are less likely to back any specific ideas for doing so—which at this point would require massive tax increases or huge spending cuts, and probably a combination of both.

Republicans spent the first half of this decade burnishing their credentials as deficit hawks. For a while, that worked—at least until Donald Trump was elected president.

Since 2016, the GOP has abandoned any pretense of caring about the deficit. Trump has concluded that he'll be gone before things get really bad, and the media talking heads who drove much of the "screw you, cut spending" mentality during the Obama years have given up, too.

And let's be clear, it is mostly a spending problem. In the fiscal year that ended on September 30 of this year, federal tax revenues increased by 4 percent but the deficit exploded because spending increased by more than 8 percent. That's simply unsustainable.

Meanwhile, most of the Democrats running for president are promising to make the deficit worse by expanding entitlements and spending vast sums of money. One of the few exceptions to that rule is Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, who might be new enough to national politics to actually have some awareness of mathematics or economics.

"My party's not known for worrying about the deficit or the debt too much but it's time for us to start getting into that," Mayor Pete says in NH town hall in response to voter anxious about debt. Says everything his campaign has proposed is paid for.

— Liz Goodwin (@lizcgoodwin) December 5, 2019

That's a message Buttigieg is starting to deliver with regularity. He was the only candidate to talk about the deficit at last week's primary debate, and he recently told The Washington Post's editorial board that "we need to recognize that we're approaching a point where you can't ignore spending we need to do on infrastructure and safety net and health and education being crowded by debt service."

Buttigieg has been attacked by the Democratic Party's left wing for merely suggesting that the deficit might be something worth talking about. But if the polls are to be believed, he might be onto something.

It's probably foolish to hope that a discussion about the national debt will break through the culture wars, impeachment battles, and whatever Twitter fights Trump starts in 2020. But voters are signaling that they don't like the current status of rising, seemingly unsolvable budget deficits. Even if voters weren't concerned, the issue is too important to ignore.

Comments

Post a Comment