God Mode

Illustration by Jason Raish.

I used to work at a large multinational media corporation that desperately wanted to be a tech start-up. “Data,” “metrics,” and “product” were the terms du jour: They drove, however ambiguously or cynically, many of the decisions made by the magazine makers and website producers who paid me to line-edit what throughout the industry is now simply called “content.” The company’s coders were poached from prestigious firms to build publishing-focused software, and their offices, located a few floors below ours, offered a cornucopia of amenities that exceeded those of the “content producers”: They had higher salaries, nicer workstations, the presumption of job security, and free snacks. They seemed to be trusted with the future of the company, responsible for creating tools to help us publish our stories and decode the data that came back to us about our readers. In meeting after meeting, low-ranking executives, accompanied by these code jockeys, would instruct editors on how to game SEO and social media algorithms, reminding us about the need to remain vigilant in the face of an ever-changing media landscape. No one really seemed to know how to fix the ailing media company, but that didn’t prevent anyone from religiously paying tithes to the very technologies undermining our shared industry.1

Ad PolicyBooks in Review

When I wasn’t at work stressing out over the ticker counters that gave value to my toil, I was still trapped in this world. I looked at my feeds when I woke up, trawling through the news, memes, and life events; I swiped between photos of strangers on dating apps; and I signed away the rights to my privacy and image with each new app I downloaded. Sometimes I would accept invitations to parties from friends on the very social media apps that were ruining my industry, and I would find myself in penthouses owned by early employees of what were known in the tech world as “unicorns”—start-ups with a valuation of $1 billion or more. Feeling flattered and, at the same time, guilty to be invited, I would spend a lot of time gawking at the excess: free drugs, alcohol, and hired help. I would think that no one, especially no twentysomethings, should be this rich. I still partook in the luxuries on offer. Surrounded by my college-educated peers who had done the smart thing and sold out, I wondered if being an editor and writer was worth the trouble. I knew I wasn’t alone in this, because a lot of my friends who came of economic age after 2008 were asking the same thing. Precarious, overeducated, and complicit in a rigged economic system we knew was undermining our own work, we wondered why we hadn’t all sent in job applications to the next hot tech company. (I did, to be honest, and was rejected.)2

In Uncanny Valley, a remarkable memoir of her nearly five years working in San Francisco’s start-up scene, Anna Wiener tells us what happens when you do end up in the tech world—and about the anguish it has caused. A liberal-arts-educated East Coaster and erstwhile denizen of New York’s literary scene, Wiener provides an achingly relatable and sharply focused firsthand account of how a set of “ambitious, aggressive, arrogant young men from America’s soft suburbs,” backed by vast capital investments and armed with data analytics technology, helped to refashion not just our economy but also our culture, aesthetics, and politics with the new digital tools they produced.3

At the center of Wiener’s narrative is a story about a generation: For her, the great innovation of the young people behind the continuing second dot-com bubble has been to persuade the rest of the world to fetishize the prophetic power of data and to get us to trade away privacy for optimization. But as an employee guiltily benefiting from this gold rush, she gives us a cautionary tale about the dangerous work cultures these tech companies cultivated as well. While warning about the collection of data and the way it reaffirms some of the most invidious forms of inequality in our society, she examines how tech companies were run on a toxic cocktail of misogyny, prejudice, and rampant surveillance. Unlike several other recent nonfiction dispatches from Silicon Valley, her book is less interested in making sense of the tech boom through the eyes and foibles of start-up founders and more concerned with asking questions from the point of view of the young people they employed. Although her memoir charts her eventual escape from this world, it also reminds us that even if we don’t work in tech and refuse to engage with the world that start-ups have created, we still need something far greater than rejection to resolve these issues. In this way, Wiener’s book, while not explicitly political, gives us a road map to the ways we can turn our growing dissatisfaction with what tech has wrought into the backbone of an ideology.4

Before 2013, when she plunged headfirst into the start-up scene, Wiener was an assistant at a middling Manhattan-based literary agency, making $30,000 a year without benefits. This kind of job is not unfamiliar to anyone who has worked in publishing or journalism. It’s an effective dead end: Often the only forms of advancement come from extrinsic forces. One could, as Wiener notes, move up by being able to “[inherit] money, marry rich, or wait for peers to defect or die.” None of these seemed likely to be happening soon, so she began to wonder if securing advance reader copies and enjoying the shabby glow of cultural capital—even while scraping to pay the rent each month—was really enough. Then one day she read an article about an e-book start-up that had raised $3 million in seed funding.5

The start-up’s mild form of disruption was simple: Seeking to turn once public goods like library books into a private, curated service, it planned to offer “access to a sprawling library of e-books for a modest monthly fee.” For Wiener, the money that might come from working at such a company had its appeal, and this particular start-up offered the chance to retain a connection to the analog world she loved, so she wanted in. No one can live off “taste and integrity” alone, she tells us, and when she was offered a three-month trial run with the company, she accepted.6

Working as a kind of do-it-all assistant for the company’s four-person team, Wiener spent her days not learning a new profession but instead buying the employee snacks, writing copy for the website, and trying to lend her literary taste and expertise to a group of boys who did not really seem to care all that much about books. In one pitch presentation the CEO asked the staffers to consult on, she notes—to herself—that he spelled “Hemingway” wrong. In the same pitch, the CEO insisted that books are not really the point of the app they’re selling; they are monetizing a kind of lifestyle. As Weiner writes, the CEO and by extension his cofounders never really “acknowledged that the reason millennials might be interested” in buying (really renting) these experiences no longer linked to physically owning books had anything to do with “student loan debt, or the recession, or the plummeting market value of cultural products in an age of digital distribution.” They were just worried about making money.7

Current Issue

As her trial period ended, Wiener could see she was a bad fit not just with this start-up but maybe with all start-ups. She was criticized for being too nice and not assertive enough (criticisms that followed her on her journey). She wrote the e-book boys a long, heartfelt e-mail hoping to convince them that her skills were indispensable, but they let her go anyway. The guys felt bad—they meant well, after all!—and helped her parlay her experience into an interview with a start-up they thought was more exciting than their own: a data analytics company in San Francisco that industry chatter had anointed as the next unicorn.8

Wiener flew to San Francisco, and after a rather humiliating interview (she was given an LSAT practice test because the interviewer didn’t have any questions for her), she landed a customer support gig that would pay her double what she made as a literary assistant. If fitting in was the problem at her first start-up job, Wiener soon realized that she had a whole new world to master: Leaving aside the strange tech lingo and office rituals, the company she was about to work for, with its sexist and often classist workplace, would reveal how rotten the Internet industry had become. The two years she eventually spent at the analytics start-up were an eye-opener not just for her; the period also charted how an industrywide, government-supported embrace of data collection rewired the US economy and redefined life both on- and offline.9

Wiener left New York for San Francisco at just the right moment—at least for a young person with literary aspirations. In 2013, Penguin and Random House merged to become one of the largest publishing companies in the world, employing about 10,000 people, commanding a combined value of over $2 billion, and creating a vast conglomerate that could affect the livelihoods of smaller houses, writers, and workers around the planet. But the mega publishing house was no match for what else was happening in the US economy. Not long before, Facebook went public with a valuation north of $100 billion, and Amazon facilitated one-half of all book sales. Amazon was also running an even more “lucrative sister business,” Wiener writes, of “selling cloud-computing services—metered use of a sprawling, international network of server farms—which provided the back-end infrastructure for other companies’ websites and apps.” In earlier eras, this kind of infrastructure might have been built by and for the public, but now it was privately owned and rented out, making it “nearly impossible to use the internet at all without enriching” Amazon. In the ecosystem Wiener was about to immerse herself in, Amazon’s ruthless and ingenious business model was much admired and provided a way to understand the world that start-ups were helping to create. It operated with the idea that there was no “crisis” in this vision of the future, “only opportunities.”10

Wiener’s new start-up job focused on helping the data analytics company’s clients troubleshoot problems with the implementation of the company’s products, a powerful suite of tools designed to help websites and apps collect user data. Quickly, Wiener realized the tools for data collection weren’t the only things for sale. For the company’s clients, user data, as much as any of the services on offer, was itself a valuable good that could be packaged and sold. “The right findings,” Wiener tells us, “could be golden, inspiring new products, or revealing user psychology, or engendering ingenious, hypertargeted advertising campaigns.” To turn these insights into an economic windfall, the analytics start-up divided the data that its clients collected into highly granular morsels. Clients could break down and segment user engagement in a way that enabled them to predict user behavior and either sell this information to other companies or retain it for their own projects.11

Related Article

The start-up’s employees were expected not to snoop around the private information that they were enabling clients to collect. But by using a setting called “God mode,” Wiener implies, she and her colleagues could easily “look up individual profiles of our lovers and family members and co-workers in the data sets belonging to dating apps and shopping services and fitness trackers and travel sites” that worked with the start-up. Even if there was an ironclad rule against such prying, Wiener continues, she’d heard stories of people at other start-ups not acting with such discretion. At a ride-sharing company, employees would frequently “search customers’ ride histories, tracking the travel patterns of celebrities and politicians.”12

With this power at her disposal, Wiener not only learned how widespread data collection had become but also began to grow a bit paranoid. “It wasn’t the act of data collection” that gave her pause, she writes; she was already resigned to that. What disturbed her was “the people who might see [her data] on the other end—people [like her].” She “never knew with whom [she] was sharing” information, and soon she began to see how the collection was not just a business strategy but something far more dangerous. It created a wealth of unchecked power for those companies that ended up with its vatic information. If they could predict user preferences and behavior, they could also manipulate the entire economy.13

Still, in her early days at the analytics company, Wiener tried to brush away many of these fears. The money was just too good, and for the first time in her adult life she was saving and climbing a career ladder. Even when a grave new development connected Silicon Valley with the upper echelons of the US government’s War on Terrorism, she didn’t at first see how the work she did was implicated.14

On the day Edward Snowden’s NSA leaks became public, Wiener and her coworkers weren’t particularly interested: “In general, we rarely discussed the news, and we certainly weren’t about to start with this story. We didn’t think of ourselves as participating in the surveillance economy. We weren’t thinking about our role in facilitating and normalizing the creation of unregulated, privately held databases on human behavior.” But Wiener’s growing unease was vindicated. Not only corporations but our government (and others around the world) were now wielding these powers to spy on their citizens and enemies alike on a scale never seen before. “We facilitated the collection of the information,” a former coworker tells her, “and we have no idea how it will be used and by whom. For all we know, we could have been one subpoena away from collaborating with intelligence agencies. If the reports are accurate, the veil between ad tech and state surveillance is very thin.”15

After the Snowden revelations, things began to sink in for Wiener, and Uncanny Valley tracks each step she took in connecting the dots. She moves from the rise of cloud computing (“The idea of the cloud, its implied transparency and ephemerality, concealed the physical reality: the cloud was just a network of hardware, storing data indefinitely. All hardware could be hacked”) to the links between corporations and the US national security state (“The servers of global technology companies had been penetrated and pillaged by the government. Some said the technology companies had collaborated wittingly”) to the terrible version of the Internet we all live with now. And while these passages can illuminate for readers the intersections they might not already know, they carry a tinge of paranoia that can veer into near–conspiracy theory. But in fairness to Wiener, she makes clear how jobs like hers incentivize people to be ignorant of the world around them. “It was perhaps a symptom of my myopia, my sense of security, that I was not thinking about data collection as one of the moral quandaries of our time,” she writes. “For all the industry’s talk about scale, and changing the world, I was not thinking about the broader implications. I was hardly thinking about the world at all.”16

Apart from her growing fear of the dangerous implications of data collection, Wiener was also confronted with the arrogance, classism, and misogyny of Silicon Valley’s workplaces. Without the aggression and petulance of a workplace culture that compared everything to conquest and brutality, she suggests, her colleagues might have paused to consider whether the products they worked on were directly connected to industry or government surveillance programs.17

At the data analytics company, in particular, Wiener got a crash course in the bullying rhetoric and office culture of the start-up world. The company’s internal slogan, “Down for the cause,” was used to chastise her and her coworkers if they failed to live up to the vague mandates of growth and devotion. The staffers were haunted by the company’s oracular CEO, an Indian American college dropout who talked almost exclusively in the language of war. After one happy hour hosted by the company, a coworker attempted to grope Wiener in the backseat of a cab. Another colleague made a pass at her in the middle of the workday and told her that he “loves dating Jewish women” because they are “so sensual.” While such workplace abuses are widespread across all industries, Wiener shows how the casual misogyny and truculence of her workplace—and tech businesses in general—are two of the reasons the Internet has become an unwelcoming place for women, people of color, and those who are down and out. Having refashioned the Internet in their image, start-up executives have made it a hostile environment for everyone else.18

Wiener eventually moved on to a third start-up, where she worked as a kind of content moderator, trawling reports of “pornography or neo-Nazi drivel” and determining if the posters violated the company’s free speech policies. For Wiener, this work proved to be the breaking point. The way her peers in tech treated San Francisco was another. On an unnamed blogging platform, a varying set of “engineers and aspiring entrepreneurs” captures the general mood among pigheaded tech bros there. In one post, a man compared the city’s temperamental weather to “a woman who is constantly PMSing.” In another, a tech dude joked about “monetizing homeless people by turning them into Wi-Fi hotspots” and excoriated the poor for “clinging to rent control and driving up condo prices.” One of her first realizations about her new home—and the one that stuck with her throughout her years there—was the depth of its contrasts: “I had never seen such a shameful juxtaposition of blatant suffering and affluent idealism.”19

Related Article

For Wiener, the city, the workplace, and the Internet had an appalling commonality. Wrapped up in the start-up machismo about disruption so prevalent in all these spaces was a stomach-churning disgust for the poor, for women, for basically anyone not employed by a tech company. The coders—many of whom were white and college-educated and were from middle-class homes—preferred a world that reflected their own comforts and needs and then projected those preferences not only into the workplaces that Wiener and many other women and people of color had to share with them but also into the technologies and surveillance tools that helped drive the economy. “Silicon Valley might have promoted a style of individualism,” Wiener observes, but its scale “bred homogeneity. Venture-funded, online-only, direct-to-consumer retailers had hired chatty copywriters to speak to the affluent and overextended…. Homogeneity was a small price to pay for the erasure of decision fatigue. It liberated our minds to pursue other endeavors, like work.”20

About four years after moving to San Francisco to enter the tech world, Wiener quit her last job there. She managed to escape with a nest egg of about $200,000 after exercising her stock options, around a year after the election of Donald Trump.21

The big-picture takeaways of Uncanny Valley are compelling, though they are not Wiener’s alone: For the last few years, we’ve seen a cottage industry of books detailing the personal and political effects of surveillance capitalism and tech-world excess. But the literary texture of Wiener’s narrative makes it particularly valuable as a primary document of this moment. Her voice, alternating between cool and detached and impassioned and earnest, boasts an observational precision that is devastating. It is whip smart and searingly funny, too. The book contains a six-page tour de force on Internet addiction, algorithms, and all of the attendant feelings of dread that is one of the best summations of an average day online I’ve ever read.22

There is also a powerful and often surprising combination of joy and ambivalence running through Wiener’s story. She is careful not to say that all tech is bad, all start-up bros evil, and she marvels at the magic of both understanding and deploying a line of code. She also allows space to those who upend her preconceptions of tech culture, among them her boyfriend Ian, a Google engineer, and Patrick, an erudite young start-up founder she befriends. That Wiener squeezes all of this—along with passages on urban theory, tracts on electronic dance music, and thoughts on contemporary novels—into some 275 pages is quite a feat.23

Still, it’s impossible to leave this book not feeling drained spiritually and politically, even as its wealth of knowledge helps orient the reader in a world so closely tied to the ups and downs of Bay Area billionaires. Throughout Uncanny Valley, there is a sense of crushing defeat. The world that Big Tech has given us feels almost foreordained, with few alternatives to serve as a counterweight to its dominance over the tools that facilitate everyday life. Wiener found her escape route, eventually becoming a writer for The New Yorker, where she quickly established herself as a trenchant observer of the tech industry. In this way, one can read Uncanny Valley as a Künstlerroman, a tale of our heroine returning to her literary ambitions after all. But like a lot of recent books on the hellscape that is the Internet, her personal story gives us little room to imagine how we all might escape this new, malignant, corporate-controlled space, where data collection, advertising, and surveillance are the status quo.24

For Wiener, this may be part of her goal. The clarifying anger that infuses her book also points to the larger politics that we will need if we are to make the Internet a more humane gathering place. Breaking up the Silicon Valley monopolies, unionizing their workplaces, and imposing effective new government regulations need to happen to begin fixing the Internet (and the world). Yet while she only briefly engages with the prospect of tech unionization, the entirety of the book is spent grappling with the limits of her coworkers’ and her own political imagination in the face of the tools they’ve created. She shows us all this because she knows something has to change. Uncanny Valley may tell the story, from one woman’s perspective, of how the tech industry has come close to ruining the world. But Wiener’s book is also proof that it hasn’t succeeded yet.25

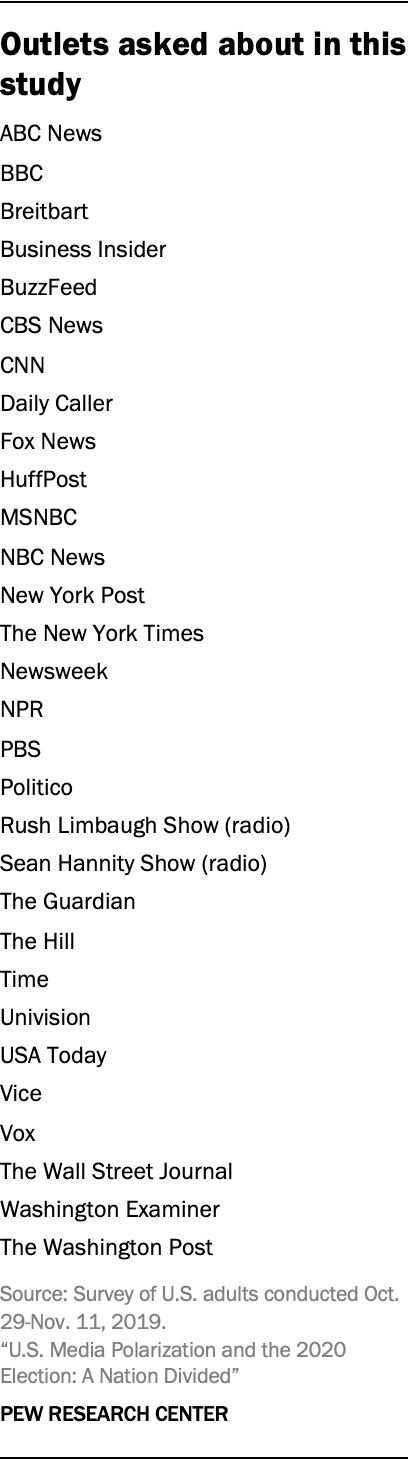

Q&A: How Pew Research Center evaluated Americans’ trust in 30 news sources

Americans are sharply divided along partisan lines when it comes to the media outlets they turn to and trust for their political and election-related news, according to a new Pew Research Center study.

Amy Mitchell, director of journalism research at Pew Research Center

Amy Mitchell, director of journalism research at Pew Research Center

More Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents trust than distrust most of the 30 outlets in the study, but the reverse is true among Republicans and GOP leaners. And while Democrats’ trust in many of these outlets has remained stable or in some cases increased since 2014, Republicans have become more alienated from some of them, widening an already substantial partisan gap.

Amy Mitchell has directed the Center’s journalism research since 2012 and oversaw the new study, which is based on an online survey of more than 12,000 U.S. adults. The study serves as the framework for our new Election News Pathways project. In this Q&A, she answers key questions about how the analysis was done and what it says about Americans’ news habits as the first votes of the 2020 presidential election cycle loom.

The study examines public trust in 30 U.S. media outlets for political and election news. How did you choose these outlets? Why weren’t some well-known outlets included? With today’s vast and fractured media landscape, our goal was not to do anything like a census. Instead, we wanted to choose a variety of news outlets with substantial audiences across different platform types. To that end, we included major broadcast and cable TV networks, public broadcasters, political radio shows, high-circulation national newspapers, high-traffic digital news outlets and international news sources with a substantial readership in the United States, among other kinds of outlets. Most of the outlets we studied were part of a similar study we published in 2014, which allowed us to track whether partisans’ trust in them changed over time.

With today’s vast and fractured media landscape, our goal was not to do anything like a census. Instead, we wanted to choose a variety of news outlets with substantial audiences across different platform types. To that end, we included major broadcast and cable TV networks, public broadcasters, political radio shows, high-circulation national newspapers, high-traffic digital news outlets and international news sources with a substantial readership in the United States, among other kinds of outlets. Most of the outlets we studied were part of a similar study we published in 2014, which allowed us to track whether partisans’ trust in them changed over time.

One group not included here are wire services like The Associated Press and Reuters. While those organizations certainly produce a great deal of original reporting, our study is not an assessment of news brands, but an analysis of outlets Americans turn to for news and the trust levels of those outlets. Most Americans get news from the wires through another news outlet that carries their syndicated content. We also took into consideration things like web traffic, topic focus and responses to open-ended survey questions about people’s main sources for political news.

Social media sites as a source for political news were asked about separately and will be a part of a future analysis.

How did you measure Americans’ trust and distrust in these outlets?

We first asked our survey respondents whether they had heard of each of the 30 outlets. If so, we asked them if they trusted it for political and election-related news. If they didn’t indicate trust in the source, we asked them if they distrusted it. After all, there’s a difference between simply not expressing trust in an outlet and actively expressing distrust of it. In cases where respondents had heard of a source but didn’t indicate that they trusted or distrusted it, we classified the response as “neither trust nor distrust.”

These questions allowed to us to measure things a few different ways. For example, we could examine trust gaps between different groups of people for different news outlets. We found that CNN is trusted by 70% of self-described liberal Democrats, but only 16% of conservative Republicans – a gap of 54 percentage points. Conversely, Fox News is trusted by 75% of conservative Republicans but only 12% of liberal Democrats – a 63-point gap.

Asking about both trust and distrust also allowed us to examine the “ratio” between these two measures for each outlet. Fox News, for instance, is among the sources in this study trusted by the largest percentage of Americans, with 43% of U.S. adults saying they trust it for political news. But it is also among the sources with the largest portion who distrust it – 40% of Americans express this view. Since that’s the case, we classified Fox News as “about equally trusted and distrusted.”

Besides asking our survey respondents about their trust and distrust in different outlets, we also asked them if they had gotten political or election-related news in the past week from any of the sources they told us they had heard of. This allowed us to surface some other interesting findings, like the fact that some Americans use news outlets even if they don’t express trust in those outlets.

How did you measure changes in trust over time?

We examined political polarization in Americans’ media habits in a major 2014 report, and since 20 of the 30 media outlets we examined in our new study were also part of the earlier report, we could assess how trust in these outlets has changed.

One of the biggest changes we saw was increased distrust among Republicans for 14 of the 20 news sources included in both studies, with particularly notable increases in distrust of CNN, The New York Times and The Washington Post – three frequent targets of criticism for President Donald Trump. While there has been far less change on the Democratic side, two exceptions are The Sean Hannity Show and Breitbart News, which are now distrusted by a larger share of Democrats than in 2014.

It’s important to point out that because of differences in methodology and survey design, the new study is not comparable in all ways with the 2014 study. For example, the new survey is representative of the total U.S. adult population, while the older survey was based only on web-using U.S. adults. And the questions asked, while similar, are not identical in all cases. But there are more points of continuity than differences, and we feel confident in the broad changes in trust and distrust that we’ve documented in the two studies.

The study refers to the audiences of different news outlets as “left-leaning,” “right-leaning” or “mixed.” How did you make these determinations? And are you saying that some of these outlets themselves are “left-leaning” or “right-leaning”?

“This study doesn’t make any determination about where news outlets themselves fall on the ideological spectrum based on either the content of their reporting, their self-identification or the views of their editorial boards.”

I’ll answer the last question first because it’s a crucial point to understand. This study doesn’t make any determination about where news outlets themselves fall on the ideological spectrum based on either the content of their reporting, their self-identification or the views of their editorial boards. This project wasn’t designed to evaluate outlets themselves or the content they produce.

Instead, we used an approach that grouped each outlet according to the ideological composition of its audience, based on where our respondents told us they get political and election-related news and how they describe themselves ideologically – liberal Democrat (including independents who lean Democratic) or conservative Republican (again including leaners). We’ve used this same system in past studies about the media.

In the new report, outlets classified as having “left-leaning” audiences are those with at least two-thirds more liberal Democrats in their audience than conservative Republicans, and outlets with “right-leaning” audiences are those with at least two-thirds more conservative Republicans than liberal Democrats. Those whose audience does not fall into either of these are classified as having more mixed audiences.

Here are three real-world examples that show this system in action. The share of Business Insider readers who identify as liberal Democrats is at least two-thirds higher than the share who identify as conservative Republicans (40% vs. 20%, or 100% larger), so we classified Business Insider as having a “left-leaning” audience. On the other end of the spectrum, the share of Washington Examiner readers who identify as conservative Republicans is at least two-thirds higher than the share who identify as liberal Democrats (44% vs. 14%, or 214% larger), so we categorized the Examiner as having a “right-leaning” audience. Then there’s the middle: The Wall Street Journal is defined as having a more “mixed” audience because the share of its readers who identify as liberal Democrats is not two-thirds higher than the share who identify as conservative Republicans (31% vs. 24%, or just 29% larger).

It’s important to keep in mind that just because we classified a news outlet as having a “left-leaning” or “right-leaning” audience does not mean that majority of its audience identifies as either liberal Democrat or conservative Republican. In fact, relatively few of the outlets we studied have audiences that consist mostly of liberal Democrats or conservative Republicans.

Why does the study include more outlets with left-leaning audiences than right-leaning audiences?

We selected these outlets based on a number of factors, including their audience size and platform type, but not based on the ideological orientation of their audiences, which we didn’t measure until later in the research process. Using this method, we ended up with 17 outlets whose audiences are left-leaning, six outlets whose audiences are right-leaning and seven outlets with mixed audiences.

One factor that may be at play here is that Republicans have a more compact media ecosystem. They rely to a large degree on a small number of outlets and view many established brands as not trustworthy. Democrats, on the other hand, rely on a wider number of outlets.

What do you hope readers will take away from this study?

It’s often tempting to use studies like this one to “rank” media outlets against one another in terms of trust or distrust, but that wasn’t the purpose of this research. Instead, we wanted to offer insight into the news sources partisans rely on for political news, and the degree to which there is common ground or division. That’s especially important in an election year like this one. (Throughout the campaign, in fact, we’ll be applying this research to do additional analyses as part of our Election News Pathways project, which will let users do their own analyses with an interactive data tool.)

Overall, these findings reveal sharp divides in the use and trust of political news sources. They don’t reveal completely separate media bubbles. There are some news sources that both Democrats and Republicans turn to, but even those areas of overlap can be hard to fully gauge since using a news source doesn’t always mean people trust it.

Who’s Afraid of the IRS? Not Facebook.

This story was originally published by ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

In March 2008, as Facebook was speeding toward 100 million users and emerging as the next big tech company, it announced an important hire. Sheryl Sandberg was leaving Google to become Facebook’s chief operating officer. CEO Mark Zuckerberg, then 23 years old, told The New York Times that Sandberg would take the young company “to the next level.”

Based on her time at Google, Sandberg soon decided that one area where Facebook was behind its peers was in its tax dodging. “My experience is that by not having a European center and running everything through the US, it is very costly in terms of taxes,” she wrote other executives in an April 2008 email, which hasn’t been previously reported. Facebook’s head of tax agreed, replying that the company needed to find “a low taxed jurisdiction to park profits.”

Later that year, Facebook named Dublin as its international headquarters, just as Google had done when Sandberg was there. And just like Google, Facebook concocted an intra-company deal to “park profits” in Ireland, where it would pay a tax rate near zero.

Like its Big Tech peers, Facebook wasn’t much afraid of the IRS. But, as it happened, the same year that Facebook started moving profits to Ireland, the IRS launched a team to crack down on deals like that. The effort started aggressively. As we recently reported, the IRS threw everything it had at Microsoft in the largest audit in the agency’s history.

But shortly after the IRS showed this new ambition, Republicans in Congress, after taking the House in 2010, began forcing cuts to the IRS’ budget. Over the years, as Facebook grew into one of the world’s largest companies, with 2 billion users, the IRS was shrinking. By the time the IRS finally took on Facebook over its Irish deal a few years later, the agency was in over its head.

ProPublica pieced together the story of the Facebook audit from court documents filed by the two sides in their yearslong battle. (Both the IRS and the company declined to comment.) The picture revealed by the documents provides a crucial window into the IRS’ struggles to check large corporations’ tax schemes.

At one point in the audit, the exam stalled for months because there was no money to hire an expert. Agents tried for five years to pick apart the deal’s complexities and were still scrambling when the statute of limitations expired in July 2016. Like a student forced, when the bell rings, to turn in a test with unanswered questions, the IRS sent Facebook the results of its incomplete audit. Based on the work it had done, the IRS thought Facebook had massively mispriced its Irish deal and should have paid billions more in taxes.

Today the fight continues before the U.S. Tax Court, and the conflict is about to reach a climax: A trial is scheduled for February, and the IRS is trying to convince a judge that it has a firm basis for its conclusions. For its part, Facebook has defended its actions in court filings, calling the IRS’ conclusions “arbitrary, capricious, or unreasonable.”

If the IRS prevails in court, it could cost Facebook up to $9 billion more in taxes, based on estimates in the company’s securities filings. It would be a notable defeat for a company that, when it comes to risky tax avoidance, has been more aggressive “than almost any other U.S. corporation,” said Matt Gardner, a senior fellow at the nonprofit Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. According to Facebook’s public filings, from 2010 through 2017 (when the U.S. corporate tax rate was 35%), the company paid a total of $3.9 billion in taxes on $50 billion of pre-tax income, a rate of about 8%.

Still, the IRS hasn’t won a clear victory in a major profit-shifting case in court for decades, said Reuven Avi-Yonah, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School and an expert on international tax. The agency, he said, has simply been “overmatched.” Given how things have gone so far in its conflict with the IRS, Facebook has good reason to be confident about the coming trial.

From the beginning in 2008, Facebook laid the foundations of its big profit shift with care, according to internal company emails disclosed by the IRS in court filings. The first step was to establish a company office in a low-tax country. Given Sandberg’s experience helping Google choose Dublin and set up its office there, Ireland was the first option. Then the question was what and who to put there. The key was having just enough of a presence in Dublin “to justify the tax benefits,” Sandberg wrote in an email at the time.

A Facebook finance executive explained that, to get “the tax advantages,” Facebook needed to transfer its intellectual property to the Dublin office. There needed to be servers there with “the key source code and user data” on them in order to “build the case” for the transfer. When a Facebook executive grumbled, “Ireland is not a first or second choice for a significant data center presence,” because it was easier to hire people in London, the tax exec responded that the Dublin center wouldn’t need to be particularly large.

In other words, it didn’t really matter how many people worked in the Dublin office. Yet, in October 2008 when Facebook publicly announced its choice of what it grandly called its “international headquarters,” Sandberg was quoted in a press release singing the praises of the Irish workforce. “After exploring various locations throughout the region, we decided Ireland was the best place,” she said. “The talent pool in Dublin is world-class and recruiting local talent will help us better understand the needs of local users.”

In a private email to an old Google colleague the previous day, however, she’d been frank. “Same decision process Google went through a long time ago,” she wrote: “tax breaks to put international revenue through. Our operations there will be very small—maybe 10 people by end of this year and 30-50 by end of next year.”

The main pieces now in place, Facebook started constructing its deal to move profits to Ireland. It set up an Irish company that declared itself to have management in the Cayman Islands. This was a trick to avoid paying even Ireland’s low 12.5% tax rate on the profits: The company would instead pay close to nothing. Now it just needed some profits. Essentially, Facebook would license its software platform to its Irish subsidiary, and this would in turn entitle the Irish subsidiary to a portion of Facebook’s profits.

IRS rules allow such intra-company deals, but the companies are supposed to arrive at a fair, “arm’s-length” price. How much the Irish company would pay for the license and what portion of Facebook’s profits the Dublin office would get—these are not numbers that companies can just make up. It doesn’t matter that the transaction was highly artificial, without any clear real-world models. The price is supposed to have some objective basis.

To conjure the prices Facebook should pay in this deal with itself, Facebook hired the giant accounting firm Ernst & Young. The firm’s experts and economists worked for years on the project. In 2011, a year after the deal had officially closed, E&Y’s team was still crunching figures and generating reports.

In September 2011, an E&Y economist emailed 600 pages of analysis to Ted Price, Facebook’s head of tax, and offered to send him three printed copies: two for his team, and one for the IRS, should the agency ever come calling. Price said that he’d take three, but they’d all be for his team. “I doubt the IRS ever even audits us on this,” he wrote. The E&Y economist replied, “knock on wood.” (In a court filing, Facebook said Price’s comment was “sarcastic.”)

The IRS began its audit, as it happened, soon afterward. But it wasn’t until 2015 that a team of agents presented preliminary findings to Facebook. The IRS thought E&Y’s estimates were off by billions of dollars. (E&Y declined to comment.)

A month later, Facebook responded with a presentation of its own that blasted the IRS’ analysis. The agency “had made significant and arbitrary errors,” Facebook later claimed in legal filings.

The IRS decided to regroup. The agency needed help, the team working the case decided, and for that, it would hire outside experts.

But there was a problem. In late 2014, Republicans in Congress had forced through a sudden $346 million cut to the IRS’ budget, and money was tight. Although billions of dollars were at stake in the Facebook audit, the IRS had no funds to hire an expert. The audit team had to wait for three months, until the new fiscal year began in October 2015, to even begin looking. Then, because of a lengthy contracting process, it took six more months for the $800,000 contract to go through. The expert, an economist who specializes in analyzing these intra-company deals, finally went to work in March 2016.

Meanwhile, the IRS was struggling to get all the documents it needed from Facebook. In January 2016, the exam team had sent off a broad request for documents about the Irish deal.

Two months later, Facebook turned over three emails in response. The company told the IRS it had “narrowly construed” the request, one of the agents on the case, Nina Wu Stone, later declared in court, and “the IRS would have to start over with issuance of a new set of [requests] if the IRS wanted a more comprehensive response.”

At the same time, the IRS feared being buried in paper. In response to another request, Facebook told the IRS the company’s systems couldn’t efficiently sort for responsive documents, and as a result, Facebook was going to turn over so much that it would “perhaps overwhelm the IRS,” as the agency put it in a court filing.

Through all of this, the clock was ticking. The IRS has three years to assess additional tax on a return, but corporate taxpayers often voluntarily extend the statute of limitations. In this case, Facebook had done so five times. Companies do this because they are hoping to avoid having to go to court.

But as the IRS began asking for more time to hire experts, Facebook decided it didn’t like where the audit was headed. The company played hardball. It offered to extend the statute again, but on one condition. The IRS had to commit that Facebook would be able to take its case to the IRS Office of Appeals.

The Office of Appeals offers taxpayers the prospect of a quiet settlement of a tax dispute, and as ProPublica reported in the story about the audit of Microsoft, large corporations often are able to obtain steep reductions in what they owe. But the IRS does have the power to block appeals. The agency rarely employs that power, but it had recently done so against other big taxpayers like Coca-Cola and Amazon. Facebook wanted to make sure that didn’t happen.

The IRS refused, and the clock continued to tick. By May 2016, with just two months left, the IRS managed to get its second expert working on the case. Nancy Bronson, an IRS supervisor, asked Facebook to reconsider an extension. That’s when Price, the Facebook executive, offered another exchange.

The IRS has a powerful tool to compel documents from large corporations that the agency thinks are dragging their feet. It’s called a “designated summons,” and it stops the clock until the taxpayer turns over all the requested documents. This can buy the IRS valuable time, but it angers corporations who must now endure added time to the audit.

Price told Bronson that Facebook would give the IRS six more months if it agreed not to use a designated summons. Again, Bronson declined. “I explained my reservations with giving up that right given the difficulties in obtaining information in a timely manner and the short period of the proposed statute extension,” she declared in a court filing.

Despite the apparent utility of designated summonses, the IRS has used them only three times since the mid-’90s. The most recent instance, against Microsoft in 2014, provoked a powerful response, and Microsoft and its corporate allies launched a lobbying campaign on Capitol Hill. Soon, lawmakers were introducing bills seeking to curtail the IRS’ use of designated summonses and other tools.

Against this added pressure, the IRS decided to take the middle path. The agency didn’t relinquish the ability to use the designated summons, but it didn’t take the aggressive step of actually using it, either. Instead, the IRS issued a conventional summons and then sued in federal district court to enforce it. This forced Facebook to turn over documents, but the clock continued to run and it would take months for Facebook to comply.

The IRS’ decision meant that it had to finish the audit without the benefit of documents that it characterized in court filings as essential to understanding Facebook’s Ireland deal. So, that’s what it did. Shortly before the statute expired, the IRS sent Facebook an official notice closing the audit. “The examination team had not completed its fact-gathering efforts when the notice was issued,” Bronson said.

The IRS concluded, based on its incomplete analysis, that Facebook’s Irish subsidiary had underpaid for Facebook’s software platform by $7 billion: The subsidiary had paid $7 billion when it should’ve paid $14 billion. If the IRS’ view prevailed, less profit would flow to Ireland and thus more income would be taxable in the U.S. As expected, Facebook soon filed a challenge in U.S. Tax Court.

The IRS said its findings weren’t absolutely final, because it could modify them in court as it acquired more evidence. But agency veterans say such changes are unusual and make the agency’s already difficult task—fighting a complex litigation battle against a better-resourced foe—even harder.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen a case where the IRS increased an assessment after it came out of exam,” said Ken Wood, a former attorney with the IRS who worked on large corporate audits. Making any sort of change is “dangerous,” he said, because it can undermine the IRS’ argument that its findings are firmly supported.

Last October, in a legal filing, the IRS disclosed that, having had time to review the millions of pages of documents that Facebook had turned over since 2016, it now thought Facebook’s Irish company should have paid $20 billion in the original transaction. However, the agency was apparently wary of shaking up its case by officially modifying its earlier findings. Confusingly, the IRS said it would argue at trial that its earlier estimate was too low, while simultaneously preserving that low estimate as the basis of the trial. The IRS wasn’t definitely saying Facebook should pay more; It was suggesting to the judge that it should.

A couple months later, just before Christmas, the IRS reversed course. It filed a motion officially changing its earlier findings and made the $20 billion valuation its one and only position at trial.

It’s unclear just how much tax Facebook’s Irish deal has saved the company, because the company has also made other moves to reduce taxes. Since Facebook refuses to divulge details, back of the envelope calculations based on other company disclosures provide the best guess. On that basis, ProPublica estimates that Facebook shifted at least $19 billion in profits offshore.

If the company’s big tax dodge were upended, Facebook could be forced to pay up to $9 billion more in taxes, the company recently said, an increase from its earlier estimates of up to $5 billion before the IRS changed its demand. But despite the increased exposure, Facebook’s chances in Tax Court are good. A win would be just another windfall for a company that’s clearly reached “the next level.”

Kirsten Berg contributed to this story.

Comments

Post a Comment